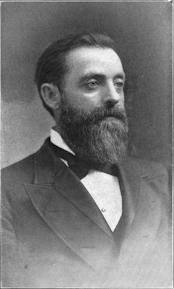

Grant’s Unsung Hero, Grenville M. Dodge, was an unlikely field commander, but turned out to be an Iowa Spymaster extraordinaire. Dodge was a former railroad builder who did not look like a soldier, according to people who knew him. They said he was a “sickly-looking fellow” and “not a man of very dignified personal presence.” But “we could very easily see that he was a man. . . that, when he went into anything, went in with his whole soul.” Grant saw in Dodge a detail oriented executive, who followed his orders to the letter. With Dodge, there was no gray, only black or white, right or wrong and when the former railroad engineer established a goal, his personnel knew, that come hell or high water, nothing could keep Dodge from completing his mission.

Grant’s Unsung Hero, Grenville M. Dodge, was an unlikely field commander, but turned out to be an Iowa Spymaster extraordinaire. Dodge was a former railroad builder who did not look like a soldier, according to people who knew him. They said he was a “sickly-looking fellow” and “not a man of very dignified personal presence.” But “we could very easily see that he was a man. . . that, when he went into anything, went in with his whole soul.” Grant saw in Dodge a detail oriented executive, who followed his orders to the letter. With Dodge, there was no gray, only black or white, right or wrong and when the former railroad engineer established a goal, his personnel knew, that come hell or high water, nothing could keep Dodge from completing his mission.

Grenville Mellen Dodge was born in Danvers, Massachusetts on April 12, 1831 to Sylvanus and Julia Theresa Phillips Dodge. From the time of his birth until he was 13 years old, Dodge moved frequently while his father tried various occupations. In 1844 the fortunes of Sylvanus Dodge improved. An ardent Democrat, he became Postmaster of the South  Danvers office and opened a bookstore. While working at a neighboring farm, the 14-year-old met the owner’s son, Frederick W. Lander, and helped him survey a railroad. Lander, who was to become a notable surveyor of the West, was impressed with Dodge and encouraged him to go to, Norwich University, a Military and Engineering School, in Vermont, and become a civil engineer. Dodge prepared for college by attending Durham Academy in New Hampshire. Despite its military discipline, the university failed to tame the young man’s spirit. Somewhat cocky, he often was in scrapes. That same trait would serve him well later in life as he dealt with railroad officials and politicians. He graduated in 1850 from Norwich, as a civil engineer and moved west working as a surveyor of railroad routes in Illinois, Iowa and Nebraska. He got married in 1854 and lived in Iowa City before moving further west to Council Bluffs in 1855. In 1856 he organized a militia company called the “Council Bluffs Guards.” In Council Bluffs, Dodge was also involved with an overland freighting company hauling cargo and supplies to Colorado. He was a co-founder of the banking firm “Baldwin and Dodge.” In addition, he worked at surveying a potential route for the Union Pacific Railroad west of Council Bluffs.

Danvers office and opened a bookstore. While working at a neighboring farm, the 14-year-old met the owner’s son, Frederick W. Lander, and helped him survey a railroad. Lander, who was to become a notable surveyor of the West, was impressed with Dodge and encouraged him to go to, Norwich University, a Military and Engineering School, in Vermont, and become a civil engineer. Dodge prepared for college by attending Durham Academy in New Hampshire. Despite its military discipline, the university failed to tame the young man’s spirit. Somewhat cocky, he often was in scrapes. That same trait would serve him well later in life as he dealt with railroad officials and politicians. He graduated in 1850 from Norwich, as a civil engineer and moved west working as a surveyor of railroad routes in Illinois, Iowa and Nebraska. He got married in 1854 and lived in Iowa City before moving further west to Council Bluffs in 1855. In 1856 he organized a militia company called the “Council Bluffs Guards.” In Council Bluffs, Dodge was also involved with an overland freighting company hauling cargo and supplies to Colorado. He was a co-founder of the banking firm “Baldwin and Dodge.” In addition, he worked at surveying a potential route for the Union Pacific Railroad west of Council Bluffs.

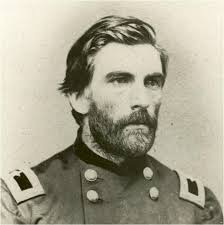

At the start of the Civil War in April 1861, Dodge was asked by Iowa Governor Samuel Kirkwood to join his staff and was assigned the task of securing weapons for the Iowa regiments organizing for service with the Union Army. Dodge traveled to Washington and was successful in obtaining 6,000 muskets for the use of Iowa troops. Upon his return to Iowa he traveled back to Council Bluffs, organized the 4th Iowa Volunteer Infantry and received a commission as colonel of the regiment in June 1861.

The regiment was ordered south to force Confederates from northern Missouri. With that mission accomplished, the 4th Iowa deployed to Arkansas and fought in the Battle of Pea Ridge in March 1862. During the battle the 4th Iowa suffered 18 killed and 135 wounded out of 300 men. Dodge suffered two wounds during the Missouri campaigns of 1861 and 1862. A thigh wound resulted when the pistol in his coat struck the saddle and discharged and the second injury occurred at Pea Ridge, when a shell severed a tree branch, striking Dodge in the head. General Grant placed him in command of the District of Corinth, Mississippi, part of Grant’s Army of Tennessee, as well as the Second Division, 16th Corps.

The regiment was ordered south to force Confederates from northern Missouri. With that mission accomplished, the 4th Iowa deployed to Arkansas and fought in the Battle of Pea Ridge in March 1862. During the battle the 4th Iowa suffered 18 killed and 135 wounded out of 300 men. Dodge suffered two wounds during the Missouri campaigns of 1861 and 1862. A thigh wound resulted when the pistol in his coat struck the saddle and discharged and the second injury occurred at Pea Ridge, when a shell severed a tree branch, striking Dodge in the head. General Grant placed him in command of the District of Corinth, Mississippi, part of Grant’s Army of Tennessee, as well as the Second Division, 16th Corps.

When Dodge was commanding out of Rolla, Missouri, he learned several lessons that would hold him and Grant in good stead at Corinth. Dodge had sent out spies to check on rumors of a Confederate attack. So far-ranging and active were they that they wore out their horses. Dodge solved this problem by keeping his undercover men out in the field to collect information in the countryside with which they were most familiar. Those living in enemy-held territory were paid for their services and expenses, although many of them refused payment because their loyalties lay with the Union. Thus was born his scouting units and a secret service that he increasingly relied upon for information. His “Corps of Scouts” was formed from men of the 24th and 25th Missouri regiments. His scouts were credited with supplying the warning of the approach of the Confederate forces of Price and Van Dorn, information that, according to one account, probably saved the Army of the Southwest from a major defeat. These trained scouts determined the numbers of the units they came across and to avoid the exaggeration that was usually attendant upon reporting enemy strength, they employed a method of measuring the length of a column along a road. They became accomplished intelligence operatives and were effective in protecting his railroad building operations from enemy cavalry harassment.

At Corinth, he took advantage of the First Tennessee Cavalry, a unit that was composed of southern men who believed in the Union cause. They knew their way around the south and passed with little trouble through Confederate lines. They could also call upon their friends and relatives living there for assistance and safe haven. Dodge also made good use of fugitive or freed slaves who also had freer access to enemy territory. He found them to be unfailingly loyal and knew of no instance when they betrayed a confidence to the enemy.

General Dodge’s office, in Corinth, had the look of a war room, maps lining the walls with precise order-of-battle and geographical information noted on them. He kept them up to date with incoming reports and used them to gain an overall picture that was invaluable when planning raids or offensives. Knowing the vulnerability of the telegraph to line tapping, he only used messengers to carry information, and then in a cipher. After incorporating information into his maps or his single communications book, he destroyed any written notes. Dodge identified some 100 secret agents by number and would not reveal their names to anyone, including his superiors. Women and blacks were among Dodge’s spies. He organized the First Alabama Colored Infantry Regiment, and the First Alabama Cavalry Regiment as agents and messengers. He also armed a detachment to guard runaway slaves. Because Southern pickets seldom stopped and questioned blacks, they made good messengers. Communications also came through wives and parents of certain regiment members.

Dodge while commanding a division in the Vicksburg campaign, had over 100 agents operating deep in the south, ranging from Mississippi and Georgia to Tennessee and Virginia, under a chief of scouts named L.A. Naron. Another of his legendary spies was Phillip Henson who did such good work scouting out enemy dispositions around Vicksburg in the spring of 1863, that Dodge presented him with a prized horse named Black Hawk. He is known to have paid two female agents for their work, Jane Featherstone in Jackson, Mississippi, and Mary Malone who traveled to Meridian, Columbus, Jackson, Okolona and Selma in the summer of 1863. For her work, Malone received $750, probably in captured Confederate money, as was the practice.

General Dodge brought security consciousness to his work, personally reading the agents’ reports and refusing to reveal their names even to his closest staff members and, in one case, to his commander. When his boss, General Stephen A. Hurlbut, insisted upon learning the names of his agents and the details of their operations, Dodge refused, specifying the harm that could befall them if their identities were not protected with the utmost security. Hurlbut, cut off funds for his intelligence network and Dodge went over his head to Grant who recognized the value of the intelligence that he was getting from Dodge, and upheld him in this matter of secrecy.

Dodge’s intelligence service was best illustrated in Grant’s campaign before Vicksburg. When Grant had to divide his force to meet the threat of an attack on his rear by Joseph H. Johnston, he was aided in knowing, thanks to Dodge’s agents, the numbers of the Confederate force were nearer to 30,000 than to the 60,000 that Johnston claimed to have. He was able to achieve an economy of force, sending just the right amount of reinforcements to Sherman. On May 16, 1863, Grant relied on Dodge’s intelligence to turn away from Johnston and mass his forces for an attack on Pemberton, driving the southerners back into the city of Vicksburg. To achieve the timely delivery of information, Dodge violated his own rules of communications security and had his agents report directly to Grant, one agent was captured and two were killed. Because of Dodge’s communications security, little is known of his intelligence organization or its efficacy. One of the unit’s major successes was the discovery and disruption of Coleman’s Scouts,

Braxton Bragg’s elite secret service unit. They captured its leader Captain Henry B. Shaw, who was going under the false name of Coleman, and several others, including Samuel Davis who was hanged as a spy after he refused to give information to Dodge’s interrogators.

Because of the intelligence his spies gave Grant at Vicksburg, Dodge was given command of the large left-wing of the Sixteenth Corps of Army of Tennessee. In the spring of 1863, fearing a court-martial for arming blacks, Dodge answered a summons to Washington. Instead, President Lincoln wanted advice on the eastern terminus of the transcontinental railroad and related matters.

For General Grant, Dodge undertook special assignments. He and his troops aided Grant and Sherman by rapidly repairing and rebuilding the railroads, bridges, and telegraph lines destroyed by the Confederates. All Dodge had at his disposal was troops, axes, picks and spades. Grant stated, “General Dodge had the work assigned to him finished within forty days of receiving his orders. The number of bridges to rebuild was 182, many of them over wide and deep chasms; the length of the road repaired was 102 miles.” Rebuilding the 150-mile Mobile and Ohio Railroad, the troops had to contend with the Confederates and guerillas ripping up track, wrecking bridges, and killing pickets. Dodge partially solved the problem by building two-story blockhouses near the bridges.

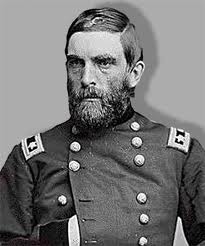

During the Atlanta campaign of 1864, Dodge commanded the 16th Army Corps, which included the 2nd, 7th, and 39th Iowa regiments. His troops held the right flank for General Sherman’s army, earning him the rank of major-general. On August 19, Dodge received a third wound that was so serious the New York newspapers reported his death. General Dodge went to his front lines and looked through a peephole in a barricade. Almost immediately a Minie ball glanced off his head, went through his hat, grazed his scalp and skull. Dodge was knocked out, fell into the trench, and was carried to the rear. Dodge had suffered a skull fracture and a severe concussion. The injury was not as serious as first thought; he was given a 30-day leave and in November he was made commander of the Department of Missouri. Two months later he was given command of the Departments of Kansas, Nebraska, Colorado and Utah.

During the Atlanta campaign of 1864, Dodge commanded the 16th Army Corps, which included the 2nd, 7th, and 39th Iowa regiments. His troops held the right flank for General Sherman’s army, earning him the rank of major-general. On August 19, Dodge received a third wound that was so serious the New York newspapers reported his death. General Dodge went to his front lines and looked through a peephole in a barricade. Almost immediately a Minie ball glanced off his head, went through his hat, grazed his scalp and skull. Dodge was knocked out, fell into the trench, and was carried to the rear. Dodge had suffered a skull fracture and a severe concussion. The injury was not as serious as first thought; he was given a 30-day leave and in November he was made commander of the Department of Missouri. Two months later he was given command of the Departments of Kansas, Nebraska, Colorado and Utah.

In the spring of 1865 Dodge was assigned to oversee the Indian campaign on the plains and protect the overland stage and freight routes to California. Dodge practiced a tough policy towards the Native Americans through psychological warfare, brutal exterminations and worthless treaties. In the 1850s the Indians had nicknamed him “Long Eye,” “Sharp Eye,” and “Hawk Eye” because he could see for miles through his surveyor’s equipment and presumably shoot as far. “Dodge’s spies constantly warned the enemy how useless it was to fight Long Eye, who, besides his other powers, could send messages long distances at great speeds over the ‘Big Medicine,’ or telegraph.” Dodge offered the Union Pacific Railroad captured Indians as laborers, who would work for food and clothes and guards to watch them. When Dodge called for volunteer troops to fight the Indians, most men said the war was over and declined the service. Five regiments of “Reconstructed Rebs” provided the necessary forces. They were made up of Southern war prisoners willing to fight Indians for their freedom. Before the Indians were eradicated, President Johnson instituted leniency and Dodge resigned from the Army effective May 30, 1866.

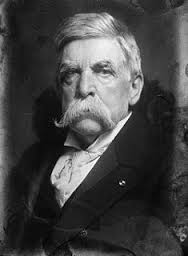

Recognizing his reputation as an accomplished leader, Iowa Republicans nominated Dodge in July 1866 for election to the U.S. Congress. After his election in November, Dodge routinely provided expert opinions on matters concerning the West, Native American policy and the reduction of the Army to a peacetime force. He declined re-nomination in 1868, but continued to be active in politics, serving as a delegate to the Republican National Convention in 1868, 1872, and 1876. Dodge also headed a commission that investigated the management of the war with Spain.

Dodge accepted a position as chief engineer for the Union Pacific railroad, the Union Pacific was constructing a transcontinental railroad that when completed would link both coasts of the United States by rail. Utilizing his talents and experience as a railroad engineer, Dodge was placed in charge of selecting and surveying the 1,186-mile route west to Promontory Point, Utah. On May 10, 1869, Dodge and Samuel Montague, the Central Pacific’s chief engineer, set the final spike of the transcontinental railroad. Resigning from his engineering position with the Union Pacific, Dodge left his 14-room mansion that overlooked the railroad and Missouri River for New York. He would live in Manhattan for the next few decades.

From the mid-1870s until his return to Council Bluffs in 1907, Dodge built and consulted on railroads in the Southwest as well as in Germany, Italy, and Russia. Dodge was President of the American, the Pacific, and the International Railway Improvement Companies and of the Missouri, Kansas and Texas Railroads. In addition, he built a line to Mexico City. He was a Director of the Union Pacific during most of the years between 1869 and 1897.” He completed his last project, the Cuba Company Railroad, in November 1902.

From the mid-1870s until his return to Council Bluffs in 1907, Dodge built and consulted on railroads in the Southwest as well as in Germany, Italy, and Russia. Dodge was President of the American, the Pacific, and the International Railway Improvement Companies and of the Missouri, Kansas and Texas Railroads. In addition, he built a line to Mexico City. He was a Director of the Union Pacific during most of the years between 1869 and 1897.” He completed his last project, the Cuba Company Railroad, in November 1902.

Retiring to Council Bluffs in 1907, Dodge spent much of his time organizing his memoirs and being active in patriotic organizations. In 1915 he fell ill with cancer and returned briefly to New York for treatment. He died in Council Bluffs on January 3, 1916 and was buried at Walnut Hill Cemetery.

Grant’s Unsung Hero, Grenville Mellen Dodge, was not only an Iowa Spymaster extraordinaire, but was an example of how a detail oriented railroad engineer and successful business entrepreneur helped ensure Union victory in the Western Theater.

Bummer

I enjoyed the way this profile showed how Civil War and western history were so closely related. Custer was far from the only character we associate with both. I knew a little bit about Dodge and was glad to have gaps in my knowledge filled in here.

Louis,

Dodge was really quite ruthless. A duck out of water in a structured military environment. Getting hit in the head at Pea Ridge and shot in the forehead in Atlanta didn’t help his disposition. Grant disbanded his unit when he went East and left Dodge to wander around the prairie. The Custer/Dodge comparison is right on. Thanks for the read!

Bummer

May 7, 1863 – Glory! Grant’s army has lept the Miss. River at Bruinsburg! It seems Vicksburg will be enveloped from the south. http://bit.ly/Y0ZH9S

Reporter,

Glad that Grant is finally across!

Bummer