Sheridan’s Jessie Scout, Arch Rowand, was not only a Stealthy Cavalry Hero, but was awarded the Medal of Honor in 1873, for acts of heroism and bravery during the winter of 1864-1865. This recommendation came directly from General Philip Sheridan, by way of Lieutenant General Grant. Originally, Rowand was one of Sheridan’s Scouts, a collection of more than 120 brave, versatile and intelligent Union soldiers who operated from August 1864 through war’s end. These risk takers helped their commander, Major General Philip H. Sheridan, lead his Army of the Shenandoah to victory in 1864 in the Shenandoah Valley and then in both the James River expedition and the Appomattox campaign in 1865. Many of the scouts wore Confederate uniforms and used forged passes and furloughs. Others passed back and forth in all manner of civilian attire. Their activities included buying information, establishing networks of Union sympathizers, intercepting enemy dispatches, conveying friendly dispatches, hunting down notorious guerrillas and engaging in desperate combat. At least 20 of the volunteer scouts became casualties, and seven earned the Medal of Honor.

Sheridan’s Jessie Scout, Arch Rowand, was not only a Stealthy Cavalry Hero, but was awarded the Medal of Honor in 1873, for acts of heroism and bravery during the winter of 1864-1865. This recommendation came directly from General Philip Sheridan, by way of Lieutenant General Grant. Originally, Rowand was one of Sheridan’s Scouts, a collection of more than 120 brave, versatile and intelligent Union soldiers who operated from August 1864 through war’s end. These risk takers helped their commander, Major General Philip H. Sheridan, lead his Army of the Shenandoah to victory in 1864 in the Shenandoah Valley and then in both the James River expedition and the Appomattox campaign in 1865. Many of the scouts wore Confederate uniforms and used forged passes and furloughs. Others passed back and forth in all manner of civilian attire. Their activities included buying information, establishing networks of Union sympathizers, intercepting enemy dispatches, conveying friendly dispatches, hunting down notorious guerrillas and engaging in desperate combat. At least 20 of the volunteer scouts became casualties, and seven earned the Medal of Honor.

Sheridan informally appointed Major Henry H. Young to reorganize the scouts, Young related, “I was ordered to take charge over the old men and organize as many men as I wanted. I picked out good men from different companies until I had about 60 men.”

Throughout the harsh winter of 1864-65, General Sheridan noted, “Not only did they bring me almost everyday intelligence from within Early’s lines but they also operated efficiently against the guerrillas infesting West Virginia.”

One of these 60, hand-picked men, deemed “Jessie Scouts” was Arch Rowand.

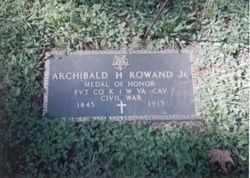

Archibald Hamilton Rowand Jr. was born in Philadelphia on March 6, 1845, and attended Quaker and other private schools in Philadelphia and Greenville, South Carolina, where his father worked as a bookbinder. Rowand’s period in South Carolina produced an ability to speak with a southern accent that served him well during the Civil War. He attempted to enlist in Pennsylvania, but was underage and went to Wheeling, West Virginia, where his father’s younger brother, Thomas Weston Rowand, a veteran of the Mexican War, was raising a company of cavalry that was soon mustered into service as Company K, 1st Virginia Volunteer Cavalry. Rowand’s enlistment date was July 17,1862, at seventeen.

Before the end of 1862, Rowand soon volunteered to be a scout, a perfect fit since he could converse easily in a Southern dialect and knew Southern expressions and customs. Most of his peers in Sheridan’s Cavalry tended to be smarter and gutsier than many other soldiers, which is one reason why they partook in the risky assignments. Arch Rowand was known for his bravery, daring and youthful recklessness. After one of his first scouting partners, Ike Harris, was killed during a trip behind enemy lines, Rowand had trouble finding another partner to join him.

In April 1863, 10 months into his service, Rowand was in the Battle of Fisher’s Hill, near Strasburg, Va., about 70 miles west of Washington, D.C. Rowand and two fellow soldiers ran into a Confederate advance guard and after skirmishing with them, drove them back to the main group of about 125 Confederate troops, at which point they had to retreat.

Rowand, a prolific letter writer, related, “Major McGee ordered a charge, but none of his men would follow him, so at first six of us followed him right into the enemy, they being stretched across the road and field; we charged into them headed by the gallant Major. We broke their ranks [and] they had started to retreat when 20 men of the third W.Va. coming up, the retreat became a rout, the rebels flying in every direction. This statement of one officer and six men breaking the rank and causing 125 rebels to retreat seems rather absurd to you I know, but it is nevertheless true.

“In the charge we lost two of our best men. Corp. Cashman was shot in the pit of the stomach, George Greene through the heart. Orderly Smith’s horse was shot in three places, Maj. McGee’s horse in the foreshoulder. I luckily escaped unharmed although in the thickest of the fight. Cashman was shot just in advance of me, Greene just behind me.

“Corp. Cashman is still living and in good spirits; the Doctor has some hopes of him. The ball went just below his ribs on the left side and lodged in his back in the right side passing between the heart and liver.”

Less than two weeks later, he wrote: “John Cashman died Sunday morning last at 4 o’clock, his wife being with him; both Cashman and Greene were young married men, both marrying since entering the service.”

Arch Rowand did relate how Major Young made some mistakes, most of the troopers were inexperienced soldiers, and the expedition was launched in bitter cold weather on January 21, 1865. At sunup the next morning, Captain George Granstaff of the 12th Virginia Cavalry watched as Major Young and a few of his men brought forth a soldier’s corpse under a flag of truce, claiming they were bringing the body to a family in New Market. Granstaff accepted the body, gave Young a meal and then watched him leave. Shortly after, the scouts burst upon the line and captured 42 men, but Granstaff and many of his troopers managed to escape.

Arch Rowand did relate how Major Young made some mistakes, most of the troopers were inexperienced soldiers, and the expedition was launched in bitter cold weather on January 21, 1865. At sunup the next morning, Captain George Granstaff of the 12th Virginia Cavalry watched as Major Young and a few of his men brought forth a soldier’s corpse under a flag of truce, claiming they were bringing the body to a family in New Market. Granstaff accepted the body, gave Young a meal and then watched him leave. Shortly after, the scouts burst upon the line and captured 42 men, but Granstaff and many of his troopers managed to escape.

Young then led his force five miles north to Woodstock, where he unaccountably sat himself down to a leisurely breakfast. Meanwhile, a Woodstock resident saw Granstaff’s band, about 200 strong, approaching the village. The resident alerted scout Archibald Rowand Jr., but Rowand could not budge Young from his meal until shots and Rebel yells were ringing in the air.

Young’s men mounted and tried to flee, but outside the town the Union column was stampeded and a melee ensued. Young’s horse was shot out from under him, and the Rebels swarmed toward the dismounted major.

Scouts Rowand, Henry ‘Pony’ Chrisman and James Campbell rushed back to help. Campbell hoisted Young up behind him, and the four rode all the way to Fisher’s Hill before the Confederate pursuit halted. In a letter home Rowand wrote of the action, “We lost all of our prisoners. Eight scouts are gone, one known to be killed, three wounded, two mortally, and four captured, only one of the captured being dressed in full gray. Have heard he was shot after being taken.”

In November of 1864, Rowand wrote home detailing one of his missions, “Yesterday I returned from inside the rebel lines. I was at Wordensville, twenty-five miles from Strasburg . . . I met a Rebel Lieut. and one man of the 18th, Va. Cav., [Confederate Gen. John] Imboden’s command, talked to him fifteen minutes, got all the information I wanted, then told him who I was. He surrendered, on being requested to. After surrendering, he wheeled his horse, and drew his revolver and attempted to run. I soon stopped him with a bullet through the spine and stomach. He died immediately. I reported to the Genl. [Philip Sheridan] what I done. He said that was very well. The Lieut. rode a splendid horse, black, which fell into my possession. Tomorrow I am going to Martinsburg [W.Va.], and will transfer him to my pocket [by selling him], as I have been out of money for some time.”

March 10, 1865, Sheridan’s forces had reached Columbia, on the James River. The Cavalry was worn and needed resupply and the general realized he had to reach the supply base at White House Landing on the Pamunkey River before his men could press on with the Army of the Potomac.

March 10, 1865, Sheridan’s forces had reached Columbia, on the James River. The Cavalry was worn and needed resupply and the general realized he had to reach the supply base at White House Landing on the Pamunkey River before his men could press on with the Army of the Potomac.

Sheridan sent two of Major Young’s scouts to travel and alert Grant. Rowand and Campbell were chosen to ride around the northern perimeter of Richmond and make their way to General Grant’s headquarters.

Rowand later wrote, that he and Campbell, “entered the enemy’s lines and passed within eight miles of Richmond…passing ourselves off for General Rosser’s scouts.” The pair made it close to the Chickahominy River before they were discovered and chased.

Upon reaching the James River, Rowand swam his horse out to a small boat and let the beast swim back to shore while he got in the vessel, picked up Campbell and made for a point north of Harrison’s Landing. They beached their skiff and walked 10 miles through the swampy forests until they came upon the Union picket line. They were then taken to City Point, where their appearance caused a considerable stir. General Grant soon had the message and quickly made arrangements to have the requisite supplies sent to White House Landing.

After the Civil War, General Sheridan took Rowand with him to New Orleans and then honorably discharged him in August of 1865. Rowand returned to Pittsburgh and worked as a railroad bookkeeper. At the age of 22, he became chief accountant of the Allegheny Valley Railroad Co. That year, he married Sarah Martha Chandler Howard, the daughter of an iron and steel executive. At the age of 33, Rowand was elected Allegheny County Clerk of Courts, and was then re-elected for another term.

In 1873, Arch Rowand would be awarded the Medal of Honor for his daring and bravery during the winter of 1864-1865.

In those days, one could become a lawyer without going to law school, Rowand studied under George Shiras Jr., a prosperous and prestigious Pittsburgh attorney and politician. Arch Rowand joined the bar in 1885 and practiced law successfully for the remainder of his life.

In 1897, Rowand lobbied the War Department to grant a Congressional Medal of Honor to his Jessie Scout partner, James Campbell for saving the life of Major Young. On Oct. 27, 1897, he received a copy of the following memorandum:

“The Secretary of War has directed the issue of a Medal of Honor to James A. Campbell, late private, Company A, 2nd New York Cavalry, the medal to be engraved as follows:

The Congress to Priv. James A. Campbell Co. A, 2nd N.Y. Cav., for gallantry near Woodstock, Va., January 22, 1865”

Archibald Hamilton Rowand died on December 14, 1913, at the age of 68 and is buried in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. A fitting eulogy was given by a close friend at his burial,

Archibald Hamilton Rowand died on December 14, 1913, at the age of 68 and is buried in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. A fitting eulogy was given by a close friend at his burial,

“There was in him a frankness, close oft to brusqueness, which betokened a

sincerity, a straightforward plainness of speech that would not flatter Neptune

for his Trident nor Jove with his power to Thunder; and what his breast forged,

that his tongue must speak.”

Sheridan’s Jessie Scout, Arch Rowand, was a Stealthy Cavalry Hero, but also a Patriotic example of America’s youth that makes this country great.

Bummer