Confederate Belle, Mary Boykin Chesnut or the Secession Queen, kept the most detailed accounts of the rise and fall of the Southern Rebellion, in her diary from 1861-1865. Really more than just a diary, one might term it a novel, painting an intimate knowledge of the inner mindset of the policy and politics of the planter-elite aristocracy, that ruled the economy and government of the southern states. Chesnut is a major player in the social landscape and can be hot-headed and opinionated. She knows that a critical analysis of the omnipotent males in her sphere, is not acceptable nor appreciated, especially by her husband or close female friends. Confederate Belle, Mary Boykin Chesnut, a beautiful, educated, out spoken, wealthy and privileged Secession Queen, leaves future generations, her first hand accounts of the end of Southern Aristocracy and the beginnings of a racial and political divide that is somewhat different 150 years after the fact.

Confederate Belle, Mary Boykin Chesnut or the Secession Queen, kept the most detailed accounts of the rise and fall of the Southern Rebellion, in her diary from 1861-1865. Really more than just a diary, one might term it a novel, painting an intimate knowledge of the inner mindset of the policy and politics of the planter-elite aristocracy, that ruled the economy and government of the southern states. Chesnut is a major player in the social landscape and can be hot-headed and opinionated. She knows that a critical analysis of the omnipotent males in her sphere, is not acceptable nor appreciated, especially by her husband or close female friends. Confederate Belle, Mary Boykin Chesnut, a beautiful, educated, out spoken, wealthy and privileged Secession Queen, leaves future generations, her first hand accounts of the end of Southern Aristocracy and the beginnings of a racial and political divide that is somewhat different 150 years after the fact.

As a young Bummer, grandmother had two volumes on her bookshelf, that were read religiously, explaining the changes that had occurred in the United States since her ancestors had migrated over the mountains into Tennessee. One, was the Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant and the other was a dog-eared copy of Chesnut’s, A Diary From Dixie. These histories, coupled with her oral history, journals and relative’s diaries, planted the seeds of an enduring appetite for more history and details of this civil upheaval and the impact on our present society. Bummer feels as if he knows Mary, as if she was a sister, her trials and heart breaks, her desperation and frustration, her despair and tragic and penniless demise. Grandmother never let the little Bummer forget the contempt she felt for the institution of slavery and that youth she read to, never forgot the truth or wisdom that was imparted by that wise and gentle elder. Enough of the History of Bummer, on to Mary Boykin Miller Chesnut, Confederate Belle.

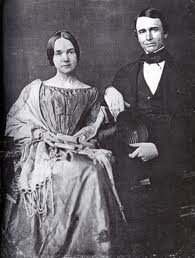

Mary Boykin Miller, was born on March 31, 1823, on her grandparents plantation near Stateburg, South Carolina. Mary’s early life was one of wealth and privilege, surrounded by state and federal politicians, she was first tutored at home and as was the custom of the rich planter elite, Mary, at 12 years old, was sent to the boarding school, Talvande’s French School for Young Ladies, in Charleston. While furthering her social graces, young Mary proved herself a brilliant pupil, mastering French and German, becoming familiar with the Classics and at 13 years of age met a dashing young gentleman, James Chesnut, Jr., who was 8 years older, than the immature teenager. At 16, Mary, started to take an interest in Chesnut and when Mary Miller turned 17, they got her parents permission and married on April 23, 1840.

Mary Boykin Miller, was born on March 31, 1823, on her grandparents plantation near Stateburg, South Carolina. Mary’s early life was one of wealth and privilege, surrounded by state and federal politicians, she was first tutored at home and as was the custom of the rich planter elite, Mary, at 12 years old, was sent to the boarding school, Talvande’s French School for Young Ladies, in Charleston. While furthering her social graces, young Mary proved herself a brilliant pupil, mastering French and German, becoming familiar with the Classics and at 13 years of age met a dashing young gentleman, James Chesnut, Jr., who was 8 years older, than the immature teenager. At 16, Mary, started to take an interest in Chesnut and when Mary Miller turned 17, they got her parents permission and married on April 23, 1840.

The Chesnut marriage was a match made in Southern Planter heaven. Both sides of the family had a long heritage of huge plantations, profitable crops, hundreds of slaves and wealthy political office and patronage connections. The young Chesnut’s first resided with his parents, but as James’ law career flourished, the couple moved to Charleston, where politics became the Chesnut’s major focus. In 1858, James was elected a United States Senator, from South Carolina and the social and power broker world of the nation’s capital loomed for Mary Chesnut.

Mary adored the power politics of Washington and threw her energies into her husband’s career. Her childlessness weighed heavily on her, but the Chesnuts were devoted to each other. Intelligent and witty, Mary took part in her husband’s career, as entertaining was an important part of building political networks. She had her best times when they were in the capitals of Washington, DC and Richmond, where friendships were begun with many politicians who would become the leading figures of the Confederate states, among them Varina and Jefferson Davis. James remained as a United States Senator until South Carolina seceded in 1860, then became an aide to President Jefferson Davis and was commissioned a Brigadier General in the Confederate Army.

Mary was appalled at a scene on the streets of Charleston and relates the following,

Mary was appalled at a scene on the streets of Charleston and relates the following,

“I have seen a negro woman sold on the block at auction. She overtopped the crowd. I was walking and felt faint, seasick. The creature looked so like my good little Nancy, a bright mulatto with a pleasant face. She was magnificently gotten up in silks and satins. She seemed delighted with it all, sometimes ogling the bidders, sometimes looking quiet, coy, and modest, but her mouth

never relaxed from its expanded grin of excitement. I dare say the poor thing knew who would buy her. I sat down on a stool in a shop and disciplined my wild thoughts. I tried it Sterne fashion. You know how women sell themselves and are

sold in marriage from queens downward, eh? You know what the Bible says about

slavery and marriage; poor women! poor slaves!”

Mary accompanied her husband to Charleston, Montgomery, Columbia, and Richmond, her drawing-room always serving as a salon for the Confederate elite. The Confederate Belle refers to a conversation with a visiting English dignitary,

“Then Mr. Browne came in with his fine English accent, so pleasant to the ear.

He tells us that Washington society is not reconciled to the Yankee régime. Mrs. Lincoln means to economize. She at once informed the majordomo that they were poor and hoped to save twelve thousand dollars every year from their salary of twenty thousand. Mr. Browne said Mr. Buchanan’s farewell was far more imposing than Lincoln’s inauguration.”

Chesnut documents the conversation of a friend who attended a Lincoln gala in Washington DC,

“Mr. Ledyard spoke to Mrs. Lincoln in behalf of a doorkeeper who almost felt he had a vested right, having been there since Jackson’s time; but met with the same answer; she had brought her own girl and must economize. Mr. Ledyard thought the twenty thousand (and little enough it is) was given to the President of these United States to enable him to live in proper style, and to maintain an establishment of such dignity as befits the head of a great nation. It is an infamy to economize with the public money and to put it into one’s private purse. Mrs. Browne was walking with me when we were airing our indignation against Mrs. Lincoln and her shabby economy. The Herald says three only of the élite Washington families attended the Inauguration Ball.”

The new President in Washington is a grand topic of ridicule and obviously misunderstood,

“In the hotel parlor we had a scene. Mrs. Scott was describing Lincoln, who is of the cleverest Yankee type. She said: “Awfully ugly, even grotesque in appearance, the kind who are always at the corner stores, sitting on boxes, whittling sticks, and telling stories as funny as they are vulgar.” Here I interposed: “But Stephen A. Douglas said one day to Mr. Chesnut, ‘Lincoln is the hardest fellow to handle I have ever encountered yet.’ ” Mr. Scott is from California, and said Lincoln is “an utter American specimen, coarse, rouge, and strong; a good-natured, kind creature; as pleasant-tempered as he is clever, and if this country can be joked and laughed out of its rights he is the kind-hearted fellow to do it. Now if there is a war and it pinches the Yankee pocket instead of filling it – “

Mary Chesnut writes in her diary of the bombardment of Fort Sumter,

“April 12th. – Anderson will not capitulate. Yesterday’s was the merriest, maddest dinner we have had yet. Men were audaciously wise and witty. We had an unspoken foreboding that it was to be our last pleasant meeting. Mr. Miles dined with us to-day. Mrs. Henry King rushed in saying, “The news, I come for the latest news. All the men of the King family are on the Island,” of which fact she seemed proud.

While she was here our peace negotiator, or envoy, came in – that is, Mr. Chesnut returned. His interview with Colonel Anderson had been deeply interesting, but Mr. Chesnut was not inclined to be communicative. He wanted his dinner. He felt for Anderson and had telegraphed to President Davis for instructions – what answer to give Anderson, etc. He has now gone back to Fort Sumter with additional instructions. When they were about to leave the wharf A. H. Boykin sprang into the boat in great excitement. He thought himself ill-used, with a likelihood of fighting and he to be left behind!

I do not pretend to go to sleep. How can I? If Anderson does not accept terms at four, the orders are, he shall be fired upon. I count four, St. Michael’s bells chime out and I begin to hope. At half-past four the heavy booming of a cannon. I sprang out of bed, and on my knees prostrate I prayed as I never prayed before.

There was a sound of stir all over the house, pattering of feet in the corridors. All seemed hurrying one way. I put on my double-gown and a shawl and went, too. It was to the housetop. The shells were bursting. In the dark I heard a man say, “Waste of ammunition.” I knew my husband was rowing about in a boat somewhere in that dark bay, and that the shells were roofing it over, bursting toward the fort. If Anderson was obstinate, Colonel Chesnut was to order the fort on one side to open fire. Certainly fire had begun. The regular roar of the cannon, there it was. And who could tell what each volley accomplished of death and destruction?”

As the Civil War progresses and Mary Chesnut’s lifestyle deteriorates, so do the fortunes of other Confederate’s and especially the planter elite. Besides the disappearance of the woman she once was, she mourns other losses, as she records in her diary,

“Our best and bravest are under the sod; we shall have to wait till another generation grows up. Here we stand, despair in our hearts.”

Mary Chesnut has reached the end of subsistence at her rented residence in Richmond and feels she must flee to one her husband’s outlying plantations,

“May 8, 1864. – My friends crowded around me so in those last days in Richmond, I forgot the affairs of this nation utterly; though I did show faith in my Confederate country by buying poor Bones’s (my English maid’s) Confederate bonds. I gave her gold thimbles, bracelets; whatever was gold and would sell in New York or London, I gave.

My friends in Richmond grieved that I had to leave them – not half so much, however, as I did that I must come away. Those last weeks were so pleasant. No battle, no murder, no sudden death, all went merry as a marriage bell. Clever, cordial, kind, brave friends rallied around me.”

Mary relates how tragic her circumstances have become,

“My pink silk dress I have sold for $600, to be paid for in instalments, two hundred a month for three months. And I sell my eggs and butter from home for two hundred dollars a month. Does it not sound well -four hundred dollars a month regularly. But in what? In Confederate money. Hélas!”

Worried about her fate and where or when she’ll get her next meal, Mary receives an urgent message for her husband,

“April 1865 – This yellow Confederate quire of paper, my journal, blotted by entries, has been buried three days with the silver sugar-dish, teapot, milk-jug, and a few spoons and forks that follow my fortunes as I wander. With these valuables was Hood’s silver cup, which was partly crushed when he was wounded at Chickamauga.

It has been a wild three days, with aides galloping around with messages, Yankees hanging over us like a sword of Damocles. We have been in queer straits. We sat up at Mrs. Bedon’s dressed, without once going to bed for forty-eight hours, and we were aweary.

Colonel Cadwallader Jones came with a despatch, a sealed secret despatch. It was for General Chesnut. I opened it. Lincoln, old Abe Lincoln, has been killed, murdered, and Seward wounded! Why? By whom? It is simply maddening, all this.

I sent off messenger after messenger for General Chesnut. I have not the faintest idea where he is, but I know this foul murder will bring upon us worse miseries. Mary Darby says, “But they murdered him themselves. No Confederates are in Washington.” “But if they see fit to accuse us of instigating it?” “Who murdered him? Who knows?” “See if they don’t take vengeance on us, now that we are ruined and can not repel them any longer.”

Following the war, the Chesnuts returned to Camden and worked unsuccessfully to extricate themselves from heavy debts. After a first abortive attempt in the 1870’s to smooth the diaries into publishable form, Mary Chesnut tried her hand at fiction, completing, three unpublished novels. James Chesnut Jr. died on February 1, 1885 and Mary, whose health had been failing for several years, followed on November 22, 1886. They lie side by side interred at Knights Hill Cemetery, Camden, South Carolina.

Following the war, the Chesnuts returned to Camden and worked unsuccessfully to extricate themselves from heavy debts. After a first abortive attempt in the 1870’s to smooth the diaries into publishable form, Mary Chesnut tried her hand at fiction, completing, three unpublished novels. James Chesnut Jr. died on February 1, 1885 and Mary, whose health had been failing for several years, followed on November 22, 1886. They lie side by side interred at Knights Hill Cemetery, Camden, South Carolina.

Confederate Belle, Mary Boykin Chesnut, may have been a Secession Queen, but her ability to document the characters, politicians, mindsets and atmosphere in the South during the Civil War, is unsurpassed and reads more like a well researched novel, than the diary of the wife of a mere Confederate politician.

Bummer

Mary Chesnut, another Civil War character I’ve been waiting to see on this blog for a while now. While I do not sympathize with the cause for which she suffered I’m at least grateful of her depiction of homefront CSA and the deprivations by war’s end.

Louis,

Been holding off on Mary, because of her position on the Confederate cause, however her bare bones portrayal of the characters and circumstances of the time are unparalleled in Southern literature. Thanks for reading.

Bummer