Confederate Racial Heritage has been passed down from generation to generation, but could one of America’s greatest stars been a bigot or just Baseball’s Georgia Peach. During the Civil War, baseball was a common denominator in both the Confederate and Union Army. In both Blue and Gray encampments, officers and enlisted, shed their blouses and competed side by side, enjoying the camaraderie of the game, a welcome relief from the boredom that often accompanied service in the field. Prisoner of War detainees in camps both North and South played baseball and even though it took the Western Theater combatants longer to become familiar with the pastime, they soon relished it’s entertaining and competitive ingredients. African-American slaves, many of whom were also fighting, embraced the game and helped spread it to other parts of the country. By the time the war had ended, black and white players were eager to play. Little is remembered of African-American troopers participating in the sport, but if it existed, a segregated version was surely played.

Confederate Racial Heritage has been passed down from generation to generation, but could one of America’s greatest stars been a bigot or just Baseball’s Georgia Peach. During the Civil War, baseball was a common denominator in both the Confederate and Union Army. In both Blue and Gray encampments, officers and enlisted, shed their blouses and competed side by side, enjoying the camaraderie of the game, a welcome relief from the boredom that often accompanied service in the field. Prisoner of War detainees in camps both North and South played baseball and even though it took the Western Theater combatants longer to become familiar with the pastime, they soon relished it’s entertaining and competitive ingredients. African-American slaves, many of whom were also fighting, embraced the game and helped spread it to other parts of the country. By the time the war had ended, black and white players were eager to play. Little is remembered of African-American troopers participating in the sport, but if it existed, a segregated version was surely played.

The game of baseball was known originally as “Townball,” and some of the rules used in the game varied, such as, the Striker (batter) gets to choose where he wants the pitch, the Pitcher must throw underhand, no leading off the bag, no base stealing, no foul lines and all balls are fair. Most games were high scoring affairs, could last for days or might be interrupted as the following contests,

“Suddenly there was a scattering of fire, which three outfielders caught the brunt; the centerfield was hit and was captured, left and right field managed to get back to our lines. The attack…was repelled without serious difficulty, but we had lost not only our centerfield, but…the only baseball in Alexandria, Texas.”

or

“It is astonishing how indifferent a person can become to danger. The report of musketry is heard but a very little distance from us…yet over there on the other side of the road most of our company, playing bat ball and perhaps in less than half an hour, they may be called to play a Ball game of a more serious nature.”

The Civil War had assured baseball’s popularity and prominence as the National Pastime. The sport’s stars of the future would carry a legacy, not only of renown, but also a possible burden of Confederate Racial Heritage that would haunt one of the greatest players, for his entire life.

Tyrus Raymond Cobb, nicknamed Ty, was born in Narrows, Georgia, in 1886 and was raised in Royston, Georgia. Ty Cobb’s great grandfather had been a Methodist Minister, who could not abide slavery, moved his family from North Carolina, to the hill country of Northeast Georgia. Ty’s grandfather, John Franklin Cobb, a farmer, had enlisted in the Confederate Army, out of North Carolina and his father, William Hershel Cobb, was a State Senator and teacher in rural Royston.

Ty Cobb lived a privileged life as a young man, but his father was a strict disciplinarian, with a quick and vicious temper. Ty’s father was shot and killed by his mother, he was 19 years old and the tragedy may have warped his temperament and reality beyond repair. At the turn of the century, Georgia was a hot bed of racial unrest and there is no evidence that Ty Cobb’s parents were racial zealots, however it would have been difficult for young Cobb to rise above the bigotry of his geographical environment.

Ty Cobb lived a privileged life as a young man, but his father was a strict disciplinarian, with a quick and vicious temper. Ty’s father was shot and killed by his mother, he was 19 years old and the tragedy may have warped his temperament and reality beyond repair. At the turn of the century, Georgia was a hot bed of racial unrest and there is no evidence that Ty Cobb’s parents were racial zealots, however it would have been difficult for young Cobb to rise above the bigotry of his geographical environment.

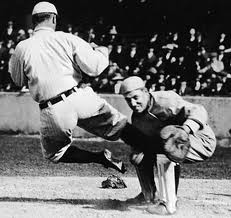

Cobb was a gifted all around athlete, with phenomenal speed and an aggressiveness that was unsurpassed. Baseball was a natural pursuit and he started playing semi-pro ball locally at 15 and then in 1905 was signed by the Detroit Tigers. Ty Cobb spent 22 years with the Tigers and played his last six with the Philadelphia Athletics. Many of his records still stand and debates continue on whether Ty Cobb was, the best of the best, all around baseball players, ever to play the game.

Ty Cobb’s aggressive and combative nature on the field, followed his social pursuits. He was a hard drinker, didn’t cotton to being pawed at and was quick to take offense at a perceived insult. He deemed it his choice, as to whom he would address or associate with and if under the influence would respond irrationally and physically. Fist, guns or knives were Ty’s weapons of choice and mostly it was a matter of honor and pride that drove his anger. Several irrational encounters with African-Americans resulted in quashed judicial proceedings and are a matter of record, testifying to a racial bent and mindset. The sports star criminal leniency, in courtroom proceedings, kept Cobb out of prison, where an ordinary citizen would have been sentenced to a lengthy incarceration.

Cobb’s anti social antics were not reserved for just citizens of color, he didn’t take fools lightly and even attacked a heckler twelve rows up in the stands during a game being played at New York, when the fan yelled that Cobb’s wife was half black. Ty charged out of the dugout and began pummeling the fan to a pulp, even after others informed him that his victim’s hands had been lost in an industrial accident. Cobb retorted, “I don’t care if he has no feet.”

Cobb’s anti social antics were not reserved for just citizens of color, he didn’t take fools lightly and even attacked a heckler twelve rows up in the stands during a game being played at New York, when the fan yelled that Cobb’s wife was half black. Ty charged out of the dugout and began pummeling the fan to a pulp, even after others informed him that his victim’s hands had been lost in an industrial accident. Cobb retorted, “I don’t care if he has no feet.”

Ty Cobb also had a gentle and generous side, an understanding for the under-dog and a humanitarian tendency, that proved that the man was a dichotomy, a traveler in the 20th century trapped in the body and soul, of a bye gone era. A master investor and businessman, he made millions of dollars in the stock market, when others were losing heavily. Cobb’s business venture’s made himself and his partners wealthy and independent. People who came in intimate contact with Cobb, both black and white, swore that he was an angel or the devil incarnate. He was a genius or a dangerous psychopath. He built hospitals and schools, left millions for educational and sports related endowments, funded retirements and annuities for his employees. Later in life, he praised the future of African-American talent in sports and endorsed individual players and their achievements.

Whether Ty Cobb was the best baseball player that ever lived or if Cobb was the beneficiary of a Confederate Racial Heritage, he will always be remembered as Baseball’s Georgia Peach.

Bummer

Ty Cobb’s story makes me think of the old Shakespeare quote about how the good we do is buried with us but the bad things live on and on. The only reason to think Ty Cobb wasn’t a racist was that white people were also targets of his hatred. Even though it’s total fantasy, I think Field of Dreams got him right when Shoeless Joe (Ray Liotta) told Ty he couldn’t play with them in the old cornfield.

Louis,

Cobb was one of Bummer’s favorites since forever. After learning about his antics off the field, couldn’t believe it at first, then wondered how he got away with most of it. Bigger than life, Ruth had a more likable public persona, Cobb was just twisted, too bad. Shakespeare hit it on the head, as usual, most of his best, taken from scripture. Cobb died a lonely and unhappy man.

Bummer