Draft Riots of 1863, were one of the most notorious acts of civil disobedience during the Civil War or was it primarily fueled by the Rampant New York Racism of the era. For five days, from Monday, July 13, until Friday, July 17, 1863, terror reigned in the streets of New York. Armed mobs protesting the first Federal conscription threatened the nation’s manufacturing and commercial center. What began as a demonstration against the draft and Abraham Lincoln’s Republican administration rapidly degenerated into bloody race riots that left at least 105 people dead. The New York City Draft Riots were by far the most violent civil disorder in 19th-century America. The widespread destruction threatened the very foundations of the Union.

Draft Riots of 1863, were one of the most notorious acts of civil disobedience during the Civil War or was it primarily fueled by the Rampant New York Racism of the era. For five days, from Monday, July 13, until Friday, July 17, 1863, terror reigned in the streets of New York. Armed mobs protesting the first Federal conscription threatened the nation’s manufacturing and commercial center. What began as a demonstration against the draft and Abraham Lincoln’s Republican administration rapidly degenerated into bloody race riots that left at least 105 people dead. The New York City Draft Riots were by far the most violent civil disorder in 19th-century America. The widespread destruction threatened the very foundations of the Union.

In July of 1863, a titanic battle between Union and Confederate forces loomed at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Fear swept New York City; if the Confederate army prevailed, southern troops could potentially invade a defenseless city within a matter of days. Fears of a Confederate plot to incite unrest in New York City and to set a series of fires further heightened New Yorker’s concerns about an imminent invasion. From the time of Lincoln’s election in 1860, the Democratic Party had warned New York’s Irish and German residents to prepare for the emancipation of slaves and the resultant labor competition when southern blacks would supposedly flee north. To these New Yorkers, the Emancipation Proclamation was confirmation of their worst fears. In March 1863, fuel was added to the fire in the form of a stricter federal draft law. All male citizens between twenty and thirty-five and all unmarried men between thirty-five and forty-five years of age were subject to military duty. The federal government entered all eligible men into a lottery. Those who could afford to hire a substitute or pay the government three hundred dollars might avoid enlistment. Blacks, who were not considered citizens, were exempt from the draft.

For the first time in American history, the Federal government imposed itself directly into the affairs of the working class. The draft act emphasized three emotional issues, rich-poor relations, black-white relations and local-federal relations, into one dynamic issue. Poor white laborers, many of them recent immigrants to the United States, felt threatened by the possible influx of cheap black labor. The rich could afford exemption. Poor whites, with some justice, felt discriminated against, which created an atmosphere that was ripe for revolt. It is also essential to assess the politics of New York City, with a particular emphasis on the Democratic political machine that held sway over New York’s large immigrant population, especially the Irish-Catholics.

In the month preceding the July 1863 lottery, in a pattern similar to the 1834 anti-abolition riots, antiwar newspaper editors published inflammatory attacks on the draft law aimed at inciting the white working class. They criticized the federal government’s intrusion into local affairs on behalf of the “nigger war.” Democratic Party leaders raised the specter of a New York deluged with southern blacks in the aftermath of the Emancipation Proclamation.

The draft began as scheduled on Saturday, July 11, and New Yorkers quickly realized that the governor and the Democrats were not going to be able to prevent conscription. Over the weekend of July 11 and 12, working people gathered in saloons, streets and kitchens to discuss their response to the draft lottery, which was scheduled to resume on Monday, July 13. As New York Herald Editor James Gordon Bennett later wrote, “Those who heard the scattered groups of laborers and mechanics who congregated in different quarters on Saturday evening…might have reasonably argued that a tumult was at hand.”

The draft began as scheduled on Saturday, July 11, and New Yorkers quickly realized that the governor and the Democrats were not going to be able to prevent conscription. Over the weekend of July 11 and 12, working people gathered in saloons, streets and kitchens to discuss their response to the draft lottery, which was scheduled to resume on Monday, July 13. As New York Herald Editor James Gordon Bennett later wrote, “Those who heard the scattered groups of laborers and mechanics who congregated in different quarters on Saturday evening…might have reasonably argued that a tumult was at hand.”

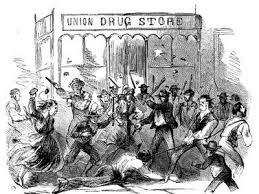

The Draft Riots began on July 13 between 6 and 7 a.m. Employees of the city’s railroads, shipyards, machine shops and ironworks and hundreds of other laborers failed to show up for work. By 8 o’clock, the workers were streaming up Eighth and Ninth avenues, closing shops, factories and construction sites and urging their workers to join them. The procession congregated in Central Park for a brief meeting, then formed into two columns that marched to the Ninth District provost marshal’s office.

German-speaking artisans and native-born Protestant journeymen, many of them volunteer firemen, a powerful political and organizational force in the city, marched alongside working-class Irish laborers; women joined with men. They banded together to express their collective outrage at the new draft law. Once they reached the Provost Marshal’s office on 46th Street and Third Avenue, the scene of Saturday’s first draft lottery, the crowd attacked the building, setting it on fire.

The destruction of the city began as rioters cut telegraph wires, collected weapons, and stopped traffic. John Kennedy, the Superintendent of Police was attacked and homes of policemen were targeted. Rioters also laid waste to jewelry, hardware, and liquor stores, eight draft offices, and the offices of Horace Greeley’s Tribune. The armory was burned, leaving several of the same rioters that started it to parish in the fire.

At 4:00 PM, protesters attacked and looted the Colored Orphan Asylum, setting it on fire, the children were safely evacuated. The rioters chased, assaulted, and lynched African-Americans throughout the city. Property belonging to African-Americans, wealthy Republicans and abolitionists were destroyed.

George Templeton Strong, was a prolific diarist who left an account of the riots from the perspective of the wealthy elite. His viewpoint, with a healthy bias against the Irish and an inability to grasp the essential motivations of the rioters, recorded his observations of the mob late Monday evening ransacking a home of a wealthy Republican family,

George Templeton Strong, was a prolific diarist who left an account of the riots from the perspective of the wealthy elite. His viewpoint, with a healthy bias against the Irish and an inability to grasp the essential motivations of the rioters, recorded his observations of the mob late Monday evening ransacking a home of a wealthy Republican family,

“The mob was in no hurry; they had no need to be; there was no one to molest them or make them afraid. The beastly ruffians were masters of the situation and of the city. After a while sporadic paving stones began to fly at windows…the rear fence was demolished and loafers were seen marching off with portable articles of furniture. I could endure the disgraceful, sickening sight no longer, and what could I do?”

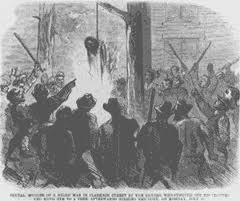

It wasn’t just a draft riot any more, it was a full-fledged race riot. William Jones, an African-American, was walking to the store to buy bread, when he was attacked by a gang led by an Irish immigrant, John Nicholson. Jones was beaten and hanged from a tree, then his body was set on fire. Peter Heuston was a Mohawk Indian, mistaken for an African-American, was beaten and died two weeks later in a hospital. After Monday, some rioters stopped, seeing how violent they had become. They even helped clean up afterwards. Others just kept on violently destroying the city that they lived in. Many African-Americans did their best to leave the city after they saw how much danger they were in.

Near the docks, tensions that had been brewing since the mid-1850s between white longshoremen and black workers boiled over. As recently as March, white employers had hired blacks as longshoremen, with whom Irish men refused to work. An Irish mob then attacked two hundred blacks who were working on the docks, while other rioters went into the streets in search of “all the negro porters, cartmen and laborers they could find.” But

in July 1863, white longshoremen took advantage of the chaos of the Draft Riots to attempt to remove all evidence of a black and interracial social life from an area near the docks. White dock workers attacked and destroyed brothels, dance halls, boarding houses, and tenements that catered to blacks; mobs stripped the clothing off the white owners of these businesses.

Rioters also made a sport of mutilating the black men’s bodies, sometimes sexually. A group of white men and boys mortally attacked black sailor William Williams, jumping on his chest, plunging a knife into him, smashing his body with stones, while a crowd of men, women, and children watched. None intervened, and when the mob was done with Williams, they cheered, pledging “vengeance on every nigger in New York.” A white laborer, George Glass, rousted black coachman Abraham Franklin from his apartment and dragged him through the streets. A crowd gathered and hanged Franklin from a lamppost as they cheered for Jefferson Davis, the Confederate president. After the mob pulled Franklin’s body from the lamppost, a sixteen-year-old Irish boy, Patrick Butler, dragged the body through the streets by its genitals. Black men who tried to defend themselves fared no better. The crowds were pitiless. After James Costello shot at and fled from a

white attacker, six white men beat, stomped, kicked, and stoned him before hanging him from a lamppost.

One of the rioters wrote in to the New York Times on the evening of July 13th attempting in part to explain his motivations to the readers:

“You will, no doubt, be hard on us rioters tomorrow morning, but that 300-dollar law has made us nobodies, vagabonds and outcasts of society, for whom no one cares when we must go to war and be shot down. We are the poor rabble, and the rich rabble is our enemy by this law. Therefore we will give our enemy battle right here, and ask no quarter. Although we got hard fists, and are dirty without, we have soft hearts, and clean consciences within…Why don’t they let the nigger kill the slave-driving race and take possession of the South, as it belongs to them.”

Harper’s summed up the transition in grim terms,

“Several buildings were sacked and burned. The Tribune was attacked, and only saved by the vigorous efforts of the police; negroes were hunted down, several were murdered under the most revolting circumstances…for a while it seemed that the city was under control of the mob…the movement, which was at first one in opposition to the draft, has developed into a scheme of plunder and robbery.”

Ironically, the most well-known center of black and interracial social life, the Five Points, was relatively quiet during the riots. Mobs neither attacked the brothels there nor killed black people within its borders. There were also instances of interracial cooperation. When a mob threatened black drugstore owner Philip White in his store at the corner of Gold and Frankfurt Street, his Irish neighbors drove the mob away, for he had often extended them credit. When rioters invaded Hart’s Alley and became trapped at its dead-end, the black and white residents of the alley together leaned out of their windows and poured

hot starch on them, driving them from the neighborhood. But such incidents were few compared to the widespread hatred of blacks expressed during the riots.

By the end of Monday, many individuals who had participated in the morning

protests, became involved in the clean-up effort; some even volunteered to help the extremely understaffed police. On Monday evening, Democratic and Republican leaders met at the St. Nicholas Hotel to find a way to end the violence. Republicans urged Mayor George Opdyke to declare martial law, while Democrats hoped for a less drastic solution. Seeking a political rather than a military resolution, Opdyke refused to request federal intervention or declare martial law.

For the next two days, the mob rioted around the clock, attacking armories, hotels, stores, newspaper offices and tenement houses. The rich were targeted as well, their homes sacked and burned. Sometimes clothes and jewelry might be taken, but mostly the mob was intent on destroying rather than stealing. Crystal chandeliers, painted portraits and pianos were hacked into little pieces.

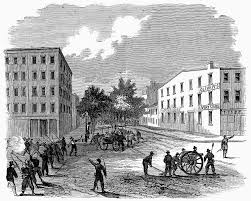

Mayor Opdyke, a Republican, sent for federal troops, but would not call for martial law, which would give control of the city to the federal government. On day 3 of the riots, General Harvey Brown and Police Commissioner Tomas Acton seemed to come by a plan to stop the rioters. Although the riots were far from over, they planned to keep the rioters in the working class neighborhoods, or the already “infected” areas of the city. Violence had spread to Staten Island and other towns close to New York City, mainly in New Jersey. By the end of Thursday, 4,000 troops were stationed in the city. They had just come from the Battle of Gettysburg and it appeared as though they kept the same mind set, as if they were in battle with the opposition. When the militia arrived, a huge mob gathered on First Avenue. They ambushed the soldiers with guns, knifes, home-made bludgeons, rocks, bricks, and any weapons they could find. Several soldiers were wounded and killed, but their defensive tactics proved much more fatal. Artillerymen fired rounds of canister and killed 30 rioters and after ten soldiers were killed or wounded, the soldiers were forced to retreat. Sergeant Charles Davids, part of the 14th New York Cavalry, was knocked off his horse and beaten to death. As soldiers were being helped and sent to a make-shift hospital, the rioters attacked again. This time, the soldiers were ready and able to hold them off. This was considered the “last battle” of the draft riots.

Mayor Opdyke, a Republican, sent for federal troops, but would not call for martial law, which would give control of the city to the federal government. On day 3 of the riots, General Harvey Brown and Police Commissioner Tomas Acton seemed to come by a plan to stop the rioters. Although the riots were far from over, they planned to keep the rioters in the working class neighborhoods, or the already “infected” areas of the city. Violence had spread to Staten Island and other towns close to New York City, mainly in New Jersey. By the end of Thursday, 4,000 troops were stationed in the city. They had just come from the Battle of Gettysburg and it appeared as though they kept the same mind set, as if they were in battle with the opposition. When the militia arrived, a huge mob gathered on First Avenue. They ambushed the soldiers with guns, knifes, home-made bludgeons, rocks, bricks, and any weapons they could find. Several soldiers were wounded and killed, but their defensive tactics proved much more fatal. Artillerymen fired rounds of canister and killed 30 rioters and after ten soldiers were killed or wounded, the soldiers were forced to retreat. Sergeant Charles Davids, part of the 14th New York Cavalry, was knocked off his horse and beaten to death. As soldiers were being helped and sent to a make-shift hospital, the rioters attacked again. This time, the soldiers were ready and able to hold them off. This was considered the “last battle” of the draft riots.

The rioters were severely punished and 67 were convicted of serious offenses and sentenced to lengthy jail terms. When the draft was resumed, the federal government stationed 10,000 troops in the city. The draft lottery took place in late August and went peaceably. The Democratic Party was able to persuade the government to reduce the lottery from 26,000 to 12,000 men. New York City’s African-American population also was reduced. Before the riots started, more than 12,000 resided in the city. After the protests in which most of the violence was directed at African-Americans, the population was recorded at less than 10,000.

New York City, with its large immigrant population, entrenched Democratic politics and deeply engrained racist traditions provided a perfect environment for the development of a violent reactionary movement. The rioters, particularly the Irish, who would bear a burden of guilt, far beyond their actual responsibility, were fueled by fears raised by the Democratic Party, journalism and a deeply engrained racism. Official records put the number of people killed at 105, however more recent research estimates the toll at 500.

The Draft Riots of 1863, were much more than just civil disobedience to a Federal Conscription Act, they were based in a Rampant New York Racism of the era, fueled by a Democratic Press and Machine Politics and the exploitation of the immigrant working class.

Bummer

Amazing how much this sounds like what we saw happen in Los Angeles in 1992, isn’t it? The technology may have changed but otherwise very similary. If you haven’t read it yet, check out Kevin Baker’s Paradise Alley, a great novel set in New York at the time of the draft riots.

Louis,

The Rodney King riots of 1992 in L.A. were a turning point for California. Major political and social change. Several business associates and the “old guy” took extreme measures in order to protect our employees and business interests just to the south. The situation was similar in many ways. Thanks for the recommendation of Paradise Alley, will check it out.

Bummer