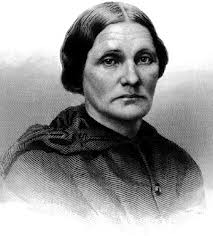

Grant’s Chief of Nursing, Mary Ann Bickerdyke, was affectionately known as Mother Bickerdyke to thousands of wounded and was definitely an unsung Union hero of the Civil War. Both Generals Ulysses S. Grant and William T. Sherman admired Bickerdyke for her bravery and for her deep concern for the soldiers. She also earned a reputation for chastising officers who failed to provide for their men. During the war, she became chief of nursing under the command of General Ulysses S. Grant.When his staff complained about the outspoken, insubordinate female nurse who consistently disregarded the army’s red tape and military procedures, Union General William T. Sherman threw up his hands and exclaimed, “She ranks me. I can’t do a thing in the world.” Bickerdyke was a nurse who ran roughshod over anyone who stood in the way of her self-appointed duties. She was known affectionately to her “boys”, the grateful enlisted men, as “Mother” Bickerdyke. When a surgeon questioned her authority to take some action, she replied, “On the authority of Lord God Almighty, have you anything that outranks that?”

Grant’s Chief of Nursing, Mary Ann Bickerdyke, was affectionately known as Mother Bickerdyke to thousands of wounded and was definitely an unsung Union hero of the Civil War. Both Generals Ulysses S. Grant and William T. Sherman admired Bickerdyke for her bravery and for her deep concern for the soldiers. She also earned a reputation for chastising officers who failed to provide for their men. During the war, she became chief of nursing under the command of General Ulysses S. Grant.When his staff complained about the outspoken, insubordinate female nurse who consistently disregarded the army’s red tape and military procedures, Union General William T. Sherman threw up his hands and exclaimed, “She ranks me. I can’t do a thing in the world.” Bickerdyke was a nurse who ran roughshod over anyone who stood in the way of her self-appointed duties. She was known affectionately to her “boys”, the grateful enlisted men, as “Mother” Bickerdyke. When a surgeon questioned her authority to take some action, she replied, “On the authority of Lord God Almighty, have you anything that outranks that?”

Mary Ann Bickerdyke was born on July 19, 1817, near Mount Vernon, Ohio. Her mother died when Mary Ann was just seventeen months old. Mary was sent to live with her grandparents and when they died she went to live with her Uncle Henry Rodgers on his farm in Hamilton County, near Cincinnati. She received only a very basic education.

When Mary Ann was just sixteen she moved to Oberlin, Ohio and she enrolled at Oberlin College, one of the few institutions of higher education open to women at that time in the United States, but did not graduate. She later returned to live with her uncle again, worked as a nurse, and assisted doctors in Cincinnati during the cholera epidemic of 1837.

When Mary Ann was just sixteen she moved to Oberlin, Ohio and she enrolled at Oberlin College, one of the few institutions of higher education open to women at that time in the United States, but did not graduate. She later returned to live with her uncle again, worked as a nurse, and assisted doctors in Cincinnati during the cholera epidemic of 1837.

In 1847, Mary Ann married Robert Bickerdyke, a sign painter and musician who was a widower with three children, and they had two boys of their own, Hiram and James. The couple moved to Galesburg, Illinois, in 1856. Robert died two years later, and their third child, Martha, died at the age of two a year after Robert’s death.

Bickerdyke was now a widow and needed to find a way to support her sons. Growing up on a farm, she had the opportunity to learn about herbs and how to use them to make medicine and she began using her botanical medicines to care for the sick in order to earn a living.

Her study of botanical medicine, which stressed the benefits of clean water, inhaling steam, wet compresses, herbal teas, healthy soups, and nature’s water in fruits and vegetables and above all cleanliness, is credited with saving many lives.

At the outbreak of the Civil War, residents of Galesburg purchased medical supplies worth five hundred dollars for soldiers serving at Cairo, Illinois. The townspeople trusted Bickerdyke to deliver these supplies. Upon arriving in Cairo, Bickerdyke used the supplies to establish a hospital for the Northern soldiers.

Seeing the horrific conditions, Bickerdyke stormed through camp, cleaning and sanitizing tents, setting up field kitchens and introducing army laundries. Where she found sick and wounded soldiers bedded on filthy straw in fetid tents, she had fresh straw spread and provided clean water and air. She had barrels cut in half so the men could bathe and dress in the clean clothes sent by the congregation.

Bickerdyke set up huge kettles over raging fires, where she brewed hot soups, porridge, tea, and coffee. She baked bread in brick ovens, and bought and bartered for eggs, milk, and fresh vegetables from the local farmers, and prepared nutritious meals in field kitchens, establishing a makeshift army hospital for Northern soldiers.

She was adamant about cleanliness, dedicated to improving the level of care and was unafraid of stepping on officer’s toes. Bickerdyke insisted on scrubbing every surface in sight, would report drunken physicians, and on one occasion ordered a staff member, who had illegally appropriated garments meant for the wounded, to strip. Though she antagonized male physicians, staff, and soldiers alike, in the name of better patient care, she won most of her fights.

Bickerdyke stayed in Cairo as an unofficial nurse, and through her unbridled energy she organized the hospitals and gained Grant’s appreciation. Grant sanctioned her efforts, and when his army moved down the Mississippi, Bickerdyke went too, setting up hospitals where they were needed. Sherman was especially fond of this volunteer nurse who followed the armies and she was the only woman he would allow in his camp. While traveling with the troops Bickerdyke suffered the same hardships and struggles as the soldiers did. The extreme cold weather, poor conditions and lack of good food and supplies was hard on everyone. When Atlanta was taken by the Union on September 2nd, Bickerdyke helped evacuate the wounded from the hospitals. By the end of the war, with the help of the U.S. Sanitary Commission, Mother Bickerdyke had built 300 hospitals and aided the wounded on 19 battlefields.

After the war ended, General’s Grant and Sherman asked Bickerdyke to participate in the Grand Review in the nation’s capital, and she led an entire corps down Pennsylvania Avenue. Sherman offered her a seat on the reviewing stand as the parade passed by, but she refused. She preferred to pass out water to the soldiers after the parade.

With the Civil War’s conclusion, Bickerdyke continued to assist Northern veterans. She provided legal assistance to veterans seeking pensions from the federal government. She also helped secure pensions for more than three hundred women nurses. Bickerdyke, herself, did not receive a pension until the 1880s. It was only twenty-five dollars per month. Bickerdyke moved to Kansas following the war, where she helped veterans to settle and begin new lives. She secured a ten thousand dollar donation from Jonathan Burr, a banker, to help the veterans obtain land, tools, and supplies. She also convinced the Chicago, Burlington, & Quincy Railroad to provide free transportation for veterans hoping to settle in Kansas. Due to Bickerdyke’s efforts, General Sherman authorized the settlers to use government wagons and teams to transport the belongings of the veterans to their new homes.

Bickerdyke remained in Kansas for most of the rest of her life. She settled in Salina, Kansas, where she opened a hotel. She continued to fight for the rights of veterans. She moved briefly to New York, before returning to Kansas with her two sons. Bickerdyke moved later to California, hoping that a change of climate would restore her declining health. She settled in San Francisco, where she accepted a position at the United States Mint. Bickerdyke eventually returned to Kansas, where she died of a minor stroke, on November 8, 1901. She was buried in Galesburg, Illinois, next to her husband.

Bickerdyke remained in Kansas for most of the rest of her life. She settled in Salina, Kansas, where she opened a hotel. She continued to fight for the rights of veterans. She moved briefly to New York, before returning to Kansas with her two sons. Bickerdyke moved later to California, hoping that a change of climate would restore her declining health. She settled in San Francisco, where she accepted a position at the United States Mint. Bickerdyke eventually returned to Kansas, where she died of a minor stroke, on November 8, 1901. She was buried in Galesburg, Illinois, next to her husband.

In 1906, a statue was erected of Mary Ann Bickerdyke, kneeling beside a wounded soldier holding a cup to his lips. It now stands in the courthouse square at Galesburg, Illinois.

Grant’s Chief of Nursing, Mary Ann Bickerdyke, is not only an American Hero, but an example of one woman’s fortitude and her devotion to the health and welfare of the soldiers that protected her country and her way of life.

Bummer