Grant’s Clandestine Operative, John C. Babcock, was unique, in that he was a Civilian Secret Agent, reporting directly to the Union Army during the Civil War. General Grant had learned early on that accurate military intelligence was the key to successful operations in the conflict with the Southern states. Actually, when General John C. Fremont commanded the Western Theater, he had created an elite contingent of mounted operatives that he named, “Jessie Scouts“, after his wife Jessie. This select group worked behind the lines, sometimes for weeks at a time, dressed in Confederate uniforms, secret handshakes, stealthy coded conversations and even neck scarves tied in elaborate knots. Grant would take Fremont’s Scouts in earnest, several months after his near defeat at Shiloh, due to misinformation gathered regarding Confederate forces that he would be facing. General Grant learned the imperative nature of gathering accurate military intelligence, the importance of stealthy Secret Agents, the alliance of Southern Unionists and behind-the-lines operatives, during his command in the Western Theater. When he finally took overall command, he found that the Civil War in the east already had a competent cast of clandestine characters, some worthy of beneficial service and some not.

Grant’s Clandestine Operative, John C. Babcock, was unique, in that he was a Civilian Secret Agent, reporting directly to the Union Army during the Civil War. General Grant had learned early on that accurate military intelligence was the key to successful operations in the conflict with the Southern states. Actually, when General John C. Fremont commanded the Western Theater, he had created an elite contingent of mounted operatives that he named, “Jessie Scouts“, after his wife Jessie. This select group worked behind the lines, sometimes for weeks at a time, dressed in Confederate uniforms, secret handshakes, stealthy coded conversations and even neck scarves tied in elaborate knots. Grant would take Fremont’s Scouts in earnest, several months after his near defeat at Shiloh, due to misinformation gathered regarding Confederate forces that he would be facing. General Grant learned the imperative nature of gathering accurate military intelligence, the importance of stealthy Secret Agents, the alliance of Southern Unionists and behind-the-lines operatives, during his command in the Western Theater. When he finally took overall command, he found that the Civil War in the east already had a competent cast of clandestine characters, some worthy of beneficial service and some not.

Before General Grant took the Eastern assignment, he developed a most unlikely Chief of Intelligence, Brigadier General Grenville Dodge. As a civilian, Dodge had been a builder of railroads and his demeanor was more the accountant, than the battlefield general. However, his tenacious spirit allowed him to develop one of the most successful military gathering networks of the Civil War. He had a spy in nearly every strategic location in the theater and the flow of information was incredible. Most of the military commanders of the era, relied on their Cavalry contingents to keep them informed of enemy locations and movements. Dodge, relied on undercover agents and Southern Unionists for information and trained his operatives in extracting accurate intelligence through interrogations of prisoners, utilizing cooperating slaves as moles and employing key transportation center officials to provide troop movements and misdirect the flow of troops and supplies. Grant had learned, through Dodge, the value of civilian clandestine operatives and the benefits they could offer to his success in the East. One of these unlikely secret agents, had once been an architect in Chicago, but now created maps for the Army, that was battling Robert E. Lee in Virginia.

Before General Grant took the Eastern assignment, he developed a most unlikely Chief of Intelligence, Brigadier General Grenville Dodge. As a civilian, Dodge had been a builder of railroads and his demeanor was more the accountant, than the battlefield general. However, his tenacious spirit allowed him to develop one of the most successful military gathering networks of the Civil War. He had a spy in nearly every strategic location in the theater and the flow of information was incredible. Most of the military commanders of the era, relied on their Cavalry contingents to keep them informed of enemy locations and movements. Dodge, relied on undercover agents and Southern Unionists for information and trained his operatives in extracting accurate intelligence through interrogations of prisoners, utilizing cooperating slaves as moles and employing key transportation center officials to provide troop movements and misdirect the flow of troops and supplies. Grant had learned, through Dodge, the value of civilian clandestine operatives and the benefits they could offer to his success in the East. One of these unlikely secret agents, had once been an architect in Chicago, but now created maps for the Army, that was battling Robert E. Lee in Virginia.

John C. Babcock, was born September 6, 1836, in Warwick, Rhode Island and moved with his parents to Chicago in 1855. As a young architect, Babcock worked at one of the most successful and prestigious design firms in Chicago and had contributed much to the architectural uniqueness of many of the mansions on Michigan Avenue. When the Civil War began John C. Babcock enlisted, as a Private, in the Sturgis Rifles, an elite Chicago Company, that had been designated, McClellan’s Bodyguard.

General McClellan had as his Chief of Intelligence, professional sleuth, extraordinaire,  Allan Pinkerton. Pinkerton was not only an asset to McClellan, but also a liability. He had worked for McClellan before the War as a railroad detective and his network of operatives were beneficial, but Pinkerton’s ability to assess military troop strengths and movements was far from adequate. In addition, the stealthy sleuth had no knowledge of topographical analysis and the benefit of such, to military strategy. McClellan discovered that he had a 25-year-old Private, named Babcock, who not only had an exceptional map making talent, but could also sketch enemy fortifications as described by deserters and returning spies. John C. Babcock found himself, in the employ of Allan Pinkerton, as a cartographer, who did his own scouting of the ground he was mapping, the only Pinkerton man who did, and his analysis was more accurate than that of the second-hand information garnered from the interrogations of prisoners and operatives. Babcock wrote his Aunt Jane that General McClellan thought that his maps were, “the finest piece of topographical work he has ever seen.”

Allan Pinkerton. Pinkerton was not only an asset to McClellan, but also a liability. He had worked for McClellan before the War as a railroad detective and his network of operatives were beneficial, but Pinkerton’s ability to assess military troop strengths and movements was far from adequate. In addition, the stealthy sleuth had no knowledge of topographical analysis and the benefit of such, to military strategy. McClellan discovered that he had a 25-year-old Private, named Babcock, who not only had an exceptional map making talent, but could also sketch enemy fortifications as described by deserters and returning spies. John C. Babcock found himself, in the employ of Allan Pinkerton, as a cartographer, who did his own scouting of the ground he was mapping, the only Pinkerton man who did, and his analysis was more accurate than that of the second-hand information garnered from the interrogations of prisoners and operatives. Babcock wrote his Aunt Jane that General McClellan thought that his maps were, “the finest piece of topographical work he has ever seen.”

Babcock soon found himself at odds with the Army’s official topographers. The regular army engineers, didn’t walk the terrain like young Babcock and his method was totally revolutionary for the era. He would map small areas in the army front, one grid at a time, eventually covering the entire line, then consolidate the maps and overlay the whole on one of Richmond and the surrounding area. Occasionally he would coordinate his mapping from observation balloons and finalize the process by having his works photographically reproduced and distributed to associated commands. One of his detailed maps found its way to President Lincoln, by way of Pinkerton, who took credit for the work and listed Babcock as his assistant.

General McClellan’s consistently slow progress aided Babcock’s work, allowing him the needed time to expand his mapping, scouting and detail. His forays into enemy territory often put the young Private in harm’s way, as he related, “I ofttimes had to run the gauntlet between a bullet and a halter.” When he was later promoted to an Intelligence Chief, he could recount that he never asked an operative to go on a scout, without knowing of the dangers that would be encountered, from his own personal experiences.

Most of John C. Babcock’s scouting and sketching took place on horseback. His faithful warhorse, Gimlet, held him in good stead and on several occasions his 4 legged companion’s speed and agility carried Babcock to safety, one stride ahead of pursuing pickets or Confederate Cavalry.

Most of John C. Babcock’s scouting and sketching took place on horseback. His faithful warhorse, Gimlet, held him in good stead and on several occasions his 4 legged companion’s speed and agility carried Babcock to safety, one stride ahead of pursuing pickets or Confederate Cavalry.

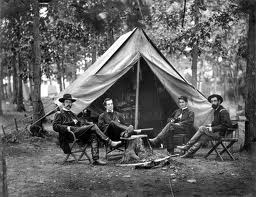

One of Babcock’s close associates was Mathew Brady photographer, Alexander Gardner, who did photographic copying for young Babcock. As a result of this relationship, the handsome scout, became one of the most publicized scouts of the Civil War, being photographed twice with intelligence luminaries and once with his trusted companion Gimlet, a curious trait for a supposedly stealthy operative.

When Lincoln finally sacked McClellan, Pinkerton also departed. They left Private Babcock behind to be mustered out with the rest of his company. As Babcock was preparing to leave for his home in Chicago, General Burnside invited the young Private to assume Pinkerton’s position. Burnside had known Babcock in Rhode Island and had become re-acquainted in Chicago, when he had sought out Babcock as an architect. John C. Babcock accepted the offer, only if he could be employed as a civilian contractor, as was Pinkerton. The youthful ex-private wrote his Aunt Jane, “I am now a free man….of as much importance in this bailiwick as though I had all the birds and stars in the heavens on my shoulders. My military ambition has settled into my pocket.” Not only was Babcock a civilian, but his monthly pay would remain the same and most would refer to him anyway as “Captain Babcock.”

As Chief of the Commander’s Secret Service, most of Babcock’s men were posted at the Central Guard House. Their civilian commander wrote of his operatives being posted at “Fort Greenhow” curbing the proclivities of “many talented and accomplished women…including the celebrated Mrs. G…..”. Of the guard-house detail Babcock related, “No pen can describe such scenes of misery cruelty and degradation that it has been my lot here to witness.”

After 3 months, Babcock was transferred to the Provost Marshal’s office, to begin work as a Pass Examiner. Finally on March 1, 1862, he was transferred to the supervision of Provost Marshal General Marsena R. Patrick. Babcock soon discovered that his history with McClellan and Pinkerton was degrading his reputation, so he bided his time reviewing and compiling Army records and performing surveillance on suspected southern infiltrators within the Union lines.

General Patrick, started consolidating his intelligence resources and recruiting experienced and stealthy operative management that could think on their feet. Patrick’s core group included, Colonel George H. Sharpe, John C. Babcock and Captain John McEntee. Patrick and his key operatives served under commanding General’s Hooker, Meade and finally Grant. Their intelligence gathering was perfected through interrogation, infiltration, a network of operatives within the Confederacy and counter-intelligence operations that disrupted troop and supply movements and an expanding Southern Unionist alliance that broke the back of native Southern loyalists.

General Patrick, started consolidating his intelligence resources and recruiting experienced and stealthy operative management that could think on their feet. Patrick’s core group included, Colonel George H. Sharpe, John C. Babcock and Captain John McEntee. Patrick and his key operatives served under commanding General’s Hooker, Meade and finally Grant. Their intelligence gathering was perfected through interrogation, infiltration, a network of operatives within the Confederacy and counter-intelligence operations that disrupted troop and supply movements and an expanding Southern Unionist alliance that broke the back of native Southern loyalists.

When General Grant took command of all Union forces he solidified the Federal Intelligence Corps and the analysis of Strategic Military Information was a precursor to the end of the civil conflict.

After the war, John C. Babcock, though a civilian and addressed as Captain, was posted in Richmond as the Chief of Police. His goal was to save as much money as possible, in order to open an architectural firm in New York City. He became a founding member of the New York Athletic Club in 1868 and went on to invent a sliding seat for competition sculling. Babcock helped design several well-known buildings and monuments in New York City. He suffered a massive stroke and died in 1908.

Grant’s Clandestine Operative, John C. Babcock, a Civilian Secret Agent was the forerunner of future Secret Service Agents, young, brilliant and with an innate ability to adapt and follow through.

Bummer

Bummer, was John Babcock any relation to Grant’s shady aide Orville Babcock?

Louis,

Don’t think Orville and John were related. Orville was born and raised in New Hampshire and John was grew up in Rhode Island and matured in Chicago. No relation according to Ancestry.Com. Thanks for the read!

Bummer