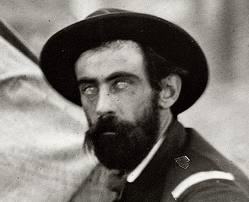

Irish Espionage Master, John C. McEntee, was not only a brave and fearless field agent for the newly formed BMI or Bureau of Military Information, but was also a Union Agent Provocateur behind Confederate lines. When lawyer turned colonel, George Henry Sharpe was officially designated Assistant Provost Marshal of the Army of the Potomac and Chief of the Bureau of Military Information, he provided a more efficient and systematic collection of military information from all sources. Sharpe appointed as his deputy John C. Babcock, previously a volunteer in the Sturgis Rifles. After his enlistment expired, Babcock became the official order-of-battle expert. It was Babcock who stayed on after Pinkerton resigned to prove that accurate information could be assembled about the enemy’s numbers. The records keeper and chief interrogator, he was the continuity in the department and now as a civilian, he was not subject to being lost when his enlistment expired. Sharpe’s third in command would be Captain John C. McEntee from the old Irish Ulster Guard of New York.

Irish Espionage Master, John C. McEntee, was not only a brave and fearless field agent for the newly formed BMI or Bureau of Military Information, but was also a Union Agent Provocateur behind Confederate lines. When lawyer turned colonel, George Henry Sharpe was officially designated Assistant Provost Marshal of the Army of the Potomac and Chief of the Bureau of Military Information, he provided a more efficient and systematic collection of military information from all sources. Sharpe appointed as his deputy John C. Babcock, previously a volunteer in the Sturgis Rifles. After his enlistment expired, Babcock became the official order-of-battle expert. It was Babcock who stayed on after Pinkerton resigned to prove that accurate information could be assembled about the enemy’s numbers. The records keeper and chief interrogator, he was the continuity in the department and now as a civilian, he was not subject to being lost when his enlistment expired. Sharpe’s third in command would be Captain John C. McEntee from the old Irish Ulster Guard of New York.

John C. McEntee was born on June 23, 1835 in Rondout, New York, the son of Irish immigrants, Charles McEntee and Christina Tremper. Young McEntee had a basic education and was enrolled at the Clinton Institute. After graduation he joined his father as a flour and feed merchant. On September 24, 1861, McEntee, at age 26, enlisted at Kingston, New York and was ranked a Quartermaster Sergeant in the reorganized Ulster regiment. Officially the regiment was part of Company S, 80th New York Infantry Regiment. Over the next two years, McEntee and his mainly Irish comrades, would see hard service at Second Bull Run, Antietam and Fredericksburg. The resultant casualties of these campaigns, created promotions for McEntee to first lieutenant and then to captain, on October 5, 1862.

McEntee, who was acquainted with Provost Marshal General Marsena Patrick, also of Irish heritage, spent the winter of 1862-1863, working in the Provost’s command and then was transferred to Sharpe’s Bureau of Military Information in April of 1863. His job would be to supervise the penetration operations, sending scouts into enemy lines and along with Babcock, develop the order of battle for Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia.

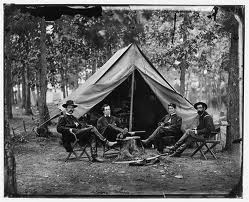

Military protocol of the era, dictated that Sharpe’s staff could direct espionage missions, but could not act as direct operatives. However, on many occasions, both McEntee and Babcock, would usually accompany details of guides or scouts on stealthy forays behind the Confederate lines. The Bureau employed some 70 “guides” to gather intelligence in the field. Using information collected from their own scouts, from liaison with the cavalry commanders, from southern refugees and deserters, from intercepted communications, from observation stations, from balloon observations, from military patrols, prisoner interrogations, liaison with other commands and from open sources like newspapers, they were able to write informed and coordinated intelligence summaries for the commander.

Military protocol of the era, dictated that Sharpe’s staff could direct espionage missions, but could not act as direct operatives. However, on many occasions, both McEntee and Babcock, would usually accompany details of guides or scouts on stealthy forays behind the Confederate lines. The Bureau employed some 70 “guides” to gather intelligence in the field. Using information collected from their own scouts, from liaison with the cavalry commanders, from southern refugees and deserters, from intercepted communications, from observation stations, from balloon observations, from military patrols, prisoner interrogations, liaison with other commands and from open sources like newspapers, they were able to write informed and coordinated intelligence summaries for the commander.

In the days prior to June 12, 1863, the Union’s Army of the Potomac was trying to determine whether General Robert E. Lee’s troops were on the move north from Culpeper or planning an attack either to the east or northeast. At midday, General Joseph Hooker sent a summary to General John Dix that Lee’s army was stationed along the banks of the Rappahannock near Culpeper and below Fredericksburg, and that Lee’s forces, along with those of Lieutenant General Richard Ewell, General James Longstreet and General J.E.B. Stuart, had been there for several days, but Hooker was unable to determine what Lee’s next move would be.

On June 12th, after escaping from his owner, slave Charlie Wright was captured near Culpeper, Virginia by the Union Army. As a matter of routine procedure, he was taken to the local Union Headquarters where he was questioned by Captain John McEntee. What Charlie Wright told McEntee that day may have prevented the capture of Washington D.C. by the Confederacy. Captain John McEntee “. . .found two Negroes who had witnessed the march – one of them a boy, but old enough to carry the organization of the Army of Northern Virginia in his head. “[he] saw Ewells (Jacksons) corps pass through that place destined for the Valley & Maryland. That Ewells corps had passed the day previous to the fight & that Longstreet was then coming up.” Now it could be seen that Lee’s forces were actually on the move northward and not stalled at Culpeper or planning an attack to the immediate east.

As was common with these types of interrogations, Wright and another young man were turned over to a different intelligence officer to see if the story could be corroborated. In this second session, not only was the information confirmed, but Wright gave exacting details such as how many days’ rations were cooked and what days the troops marched. Wright’s knowledge was so good and committed to memory, that some called him a “walking ‘order of battle’ chart.”

McEntee, immediately took the extraordinary step of sending a report directly to Union Headquarters by telegraph rather than by a courier on horseback. The telegraph stated,

“A ‘contraband’ captured last Tuesday states that he had been living at Culpeper C.H. [Court House] for some time past. Saw Ewell’s Corps passing through that place destined for the [Cumberland] Valley and Maryland…”

The information provided by Captain John McEntee was enough to convince President Lincoln that Lee, rather than launching the expected direct attack on Washington, intended to invade the North in order to attack either Pennsylvania or Baltimore. Lincoln then ignored the advice of some members of the Union Army’s General Staff by ordering the Army of the Potomac, which had been positioned to defend Washington against the anticipated attack, to instead decamp immediately and then move north. The Union Army’s orders were to parallel, or shadow, the right flank of Lee’s northward movements and position itself between Lee and Washington, DC. It was only when the main body of the Confederate Army appeared to be turning to the south that the Army of the Potomac engaged the invaders near the small Pennsylvania town of Gettysburg.

On June 13, Hooker’s forces were on the march in a parallel route to that of Lee who was looking to have his troops shielded by the Blue Ridge Mountains so that he could proceed on course uninterrupted. Through McEntee’s efforts and his ability to recognize the value of Wright’s information, the battle at Gettysburg was not just an “accidental collision” of both sides. The Union Army could protect Washington from Lee’s forces and force the Confederates to group at or near Gettysburg.

On December 19, 1864, John McEntee was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel and served the Bureau of Military Information, continuing his intelligence gathering and stealthy espionage outside Petersburg and Richmond through the end of the Civil War. He served as a provost judge of Richmond and was discharged on April 16, 1866. McEntee was employed briefly in New York and Boston before returning to Kingston to spend the rest of his career in the foundry and machine-shop business. He was one of Kingston’s leading citizens, as an alderman, library trustee and an officer in local charities. McEntee, died in Kingston on December 19, 1903 at the age of seventy-eight and is buried in Montrepose Cemetery, Kingston, New York next to his wife, Ann Eliza Dibblee.

On December 19, 1864, John McEntee was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel and served the Bureau of Military Information, continuing his intelligence gathering and stealthy espionage outside Petersburg and Richmond through the end of the Civil War. He served as a provost judge of Richmond and was discharged on April 16, 1866. McEntee was employed briefly in New York and Boston before returning to Kingston to spend the rest of his career in the foundry and machine-shop business. He was one of Kingston’s leading citizens, as an alderman, library trustee and an officer in local charities. McEntee, died in Kingston on December 19, 1903 at the age of seventy-eight and is buried in Montrepose Cemetery, Kingston, New York next to his wife, Ann Eliza Dibblee.

Irish Espionage Master, John C. McEntee, was not just another Fearless Irish Patriot, he had the grit and bravery that makes a genuine Hero and Union Agent Provocateur.

Bummer