Lincoln Assassin, John Wilkes Booth, was either a brilliant Stage Actor, a delusional, psychotic sociopath or just a pathetic Lost Cause Fanatic. Booth and his brother, Edwin, were both the illegitimate sons of renowned Shakespearean actor, Junius Brutus Booth. Raised in an elite and entitled world of fantasy and make-believe, John Wilkes Booth’s desire to achieve fame and immortality, in order to overcome the shame of his illegitimacy, resulted in a psyche that lent itself perfectly to the imaginary realm of drama and acting. The young thespian, was a Confederate zealot, despised Lincoln and railed against the idea of abolition. According to Booth his favorite Shakespearean character portrayed was Brutus, the slayer of a tyrant.

Lincoln Assassin, John Wilkes Booth, was either a brilliant Stage Actor, a delusional, psychotic sociopath or just a pathetic Lost Cause Fanatic. Booth and his brother, Edwin, were both the illegitimate sons of renowned Shakespearean actor, Junius Brutus Booth. Raised in an elite and entitled world of fantasy and make-believe, John Wilkes Booth’s desire to achieve fame and immortality, in order to overcome the shame of his illegitimacy, resulted in a psyche that lent itself perfectly to the imaginary realm of drama and acting. The young thespian, was a Confederate zealot, despised Lincoln and railed against the idea of abolition. According to Booth his favorite Shakespearean character portrayed was Brutus, the slayer of a tyrant.

John Wilkes Booth, the ninth of ten children, whose parents, actors Junius Brutus Booth and mistress Mary Ann Holmes, was born on May 10, 1838 and raised on the family farm near Bel Air, Maryland. His father, a famous actor, was a hard-drinking, eccentric, slave owner, who married Holmes in 1851, when Booth was 13. As a youth, he attended the Bel Air Academy, the Milton Boarding School for Boys and St. Timothy’s Hall, a Maryland military academy. As a student, Booth had a difficult time concentrating on academics, but excelled in athletics, especially horsemanship and fencing, often cutting himself, with his foil, during the excitement of competition.

When Booth’s father died in 1852, he quit school and practiced elocution and memorized Shakespeare, in the seclusion of the woods surrounding the family farm. The ultimate goal was to follow his brothers into a career on the stage and when he turned 17, Booth made his acting debut in Baltimore, on April 14, 1855, with a role in a production of Shakespeare’s Richard III. His early performances were such a hit that Booth was soon invited to tour the country with a Shakespearean acting company based in Richmond, Virginia. In 1858 John Wilkes Booth performed in at least 83 plays, most having as their theme the killing or overthrow of an unjust ruler.

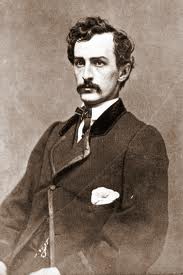

As Booth’s fame grew, many called him “the handsomest man in America.” He stood 5-8, had jet black hair, ivory skin, and was lean and athletic. He had an easy charm about him that attracted both women and men. Although not a great actor, his appearance would have garnered fans, especially among female theater goers.

As Booth’s fame grew, many called him “the handsomest man in America.” He stood 5-8, had jet black hair, ivory skin, and was lean and athletic. He had an easy charm about him that attracted both women and men. Although not a great actor, his appearance would have garnered fans, especially among female theater goers.

When the Civil War began in April of 1861, Booth was starring in Albany, New York. His zeal for the South’s secession, calling it “heroic”, so angered the local residents that they demanded his being banned from the stage for making “treasonable statements”.

In 1862, Booth made his New York debut, this time as the lead in Richard III. The New York Herald described him as a “veritable sensation.” Booth described his successful roll; “I am determined to be a villain.” While on tour, he achieved national acclaim, but a respiratory illness in 1863 meant Booth had no choice but to take a temporary leave from the stage.

In the 1850s, Booth had joined the No-Nothing Party, which aimed to limit immigration into the United States. In 1859, he showed his support for slavery by joining a Virginia Company that aided in the capture and execution of John Brown, following his raid on Harper’s Ferry. Although Booth had a deep hatred for President Lincoln and the Republican Party, he did not join the Confederate Army, instead he volunteered as a secret agent for the Confederacy and also helped smuggle medical supplies from the North to the Confederate forces in the South. As a touring actor, Booth had the perfect cover for this kind of work.

Booth was arrested in St. Louis, in early 1863, when declaring that he “wished the President and the whole damned government would go to hell.” Charged with making treasonous remarks, he was released after filing an oath of allegiance and paying a large fine.

On the night of November 9, 1863, Booth was performing in The Marble Heart , a popular melodramatic tragedy, on the stage at Ford’s Theater in Washington. Watching the play from the Presidential Box was Abraham Lincoln. The box was right next to the stage, surrounded by a railing. One of the women watching the play with the Lincolns was Mary B. Clay, daughter of the Kentucky abolitionist and minister to Russia, Cassius Clay. She later wrote,

“Twice Booth in uttering disagreeable threats in the play came very near and put his finger close to Mr. Lincoln’s face; when he came a third time I was impressed by it, and said, Mr. Lincoln, he looks as if he meant that for you. Well, he said, he does look pretty sharp at me, doesn’t he?”

In 1864, John Wilkes Booth wrote his brother-in-law,

“This country was formed for the white not for the black man. And looking upon African slavery from the same stand-point, as held by those noble framers of our Constitution, I for one, have ever considered it, one of the greatest blessings (both for themselves and us) that God ever bestowed upon a favored nation.”

In September of 1864, Booth was plotting to kidnap President Lincoln. Lincoln would be taken to Richmond and exchanged for Confederate soldiers in Union prisons. After several months, he had recruited Michael O’Laughlen, Samuel Arnold, Lewis Powell (alias Paine or Payne), John Surratt Jr., David Herold, and George Atzerodt. On March 15, 1865, Booth met with the entire group at Gautier’s Restaurant on Pennsylvania Avenue to discuss Lincoln’s abduction. Booth had learned that Lincoln would be attending a play at the Campbell Hospital just outside Washington on March 17, 1865. It seemed like an ideal time to seize Lincoln in his carriage. However, at the last-minute, the president changed his plans and did not attend the performance.

In September of 1864, Booth was plotting to kidnap President Lincoln. Lincoln would be taken to Richmond and exchanged for Confederate soldiers in Union prisons. After several months, he had recruited Michael O’Laughlen, Samuel Arnold, Lewis Powell (alias Paine or Payne), John Surratt Jr., David Herold, and George Atzerodt. On March 15, 1865, Booth met with the entire group at Gautier’s Restaurant on Pennsylvania Avenue to discuss Lincoln’s abduction. Booth had learned that Lincoln would be attending a play at the Campbell Hospital just outside Washington on March 17, 1865. It seemed like an ideal time to seize Lincoln in his carriage. However, at the last-minute, the president changed his plans and did not attend the performance.

During Lincoln’s second inaugural on March 4, 1865, Booth was present, a guest of his recent fiance, Lucy Lambert Hale, daughter of former New Hampshire Senator, John Parker Hale. Several of the conspirators were also present and Booth expressed regret for not assassinating the President when he had the chance.

During a on speech, April 11, 1865, Lincoln called for limited Negro suffrage, giving the right to vote to those who had served in the military during the war. When Booth heard these words, he muttered to his companions, “That means nigger citizenship. That is the last speech he will ever make.” He tried, unsuccessfully, to convince one of those companions to shoot the president then and there.

On April 14, 1865, John Wilkes Booth, learned that Lincoln and Grant would attend a performance at the Ford Theater, he decided to strike. He and his companions would kill the president, vice president, cabinet members and perhaps Grant as well. Booth had performed at Ford’s Theater recently, was well-known and his presence would not arouse suspicion. He gained entry to the box where Abraham and Mary Lincoln were enjoying the comedy Our American Cousin. Grant wasn’t there, only Major Rathbone and his fiancé, Clara Harris. John Parker, Lincoln’s bodyguard from the Metropolitan Police Force, had left his position outside the box to get a drink. After entering, Booth secured the door with a wooden bar and shot Lincoln from behind, the bullet entering the left side of the President’s head and lodged beneath the eye. The assassin sliced, at Rathbone with a dagger and cut a deep slice in the major’s arm, vaulted over the flag-draped rail of the box to the stage below, caught a spur on the flag and broke his leg when he landed. Witnesses related that Booth shouted, “Sic semper tyrannis” (Thus always to tyrants); others claimed he said, “The South is avenged” as he limped off the stage and out the rear of the theater to a waiting horse held by, John Burroughs, a boy who worked at the theater.

Lewis Powell had attacked Secretary Seward, stabbing him several times and although wounded severely, managed to survive. George Atzerodt, for whatever reason, never assaulted Andrew Johnson. After a brief stop to pick up supplies, Booth and David Herold left and headed for Richmond.

The two arrived at the home of Doctor Samuel Mudd early the next morning to have Booth’s leg treated. They eventually reached Port Royal, Virginia, on the morning of April 26, 1865 and hid in a barn owned by Richard Garrett. Federal troops soon arrived and Booth and Herold were ordered to surrender.

The two arrived at the home of Doctor Samuel Mudd early the next morning to have Booth’s leg treated. They eventually reached Port Royal, Virginia, on the morning of April 26, 1865 and hid in a barn owned by Richard Garrett. Federal troops soon arrived and Booth and Herold were ordered to surrender.

The officer in charge of the Federal Cavalry sent to Virginia in search of Booth was Lieutenant Edward Doherty and he relates the following of Herold’s surrender and John Wilkes Booth death,

“I dismounted, and knocked loudly at the front door. Old Mr. Garrett came out. I seized him, and asked him where the men were who had gone to the woods when the cavalry passed the previous afternoon. While I was speaking with him some of the men had entered the house to search it. Soon one of the soldiers sang out, ‘O Lieutenant! I have a man here I found in the corn-crib.’ It was young Garrett, and I demanded the whereabouts of the fugitives. He replied, ‘In the barn.’ Leaving a few men around the house, we proceeded in the direction of the barn, which we surrounded. I kicked on the door of the barn several times without receiving a reply. Meantime another son of the Garrett’s had been captured. The barn was secured with a padlock, and young Garrett carried the key. I unlocked the door, and again summoned the inmates of the building to surrender. At this moment Herold reached the door. I asked him to hand out his arms; he replied that he had none. I told him I knew exactly what weapons he had. Booth replied, ‘I own all the arms, and may have to use them on you, gentlemen.’ I then said to Herold, ‘Let me see your hands.’ He put them through the partly opened door and I seized him by the wrists. I handed him over to a non-commissioned officer. Just at this moment I heard a shot, and thought Booth had shot himself. Throwing open the door, I saw that the straw and hay behind Booth were on fire. He was half-turning towards it. He had a crutch, and he held a carbine in his hand. I rushed into the burning barn, followed by my men, and as he was falling caught him under the arms and pulled him out of the barn. The burning building becoming too hot, I had him carried to the veranda of Garrett’s house.

Booth received his death-shot in this manner. While I was taking Herold out of the barn one of the detectives went to the rear, and pulling out some protruding straw set fire to it. I had placed Sergeant Boston Corbett at a large crack in the side of the barn, and he, seeing by the igniting hay that Booth was leveling his carbine at either Herold or myself, fired, to disable him in the arm; but Booth making a sudden move, the aim erred, and the bullet struck Booth in the back of the head, about an inch below the spot where his shot had entered the head of Mr. Lincoln. Booth asked me by signs to raise his hands. I lifted them up and he gasped, ‘Useless, useless!’ We gave him brandy and water, but he could not swallow it. I sent to Port Royal for a physician, who could do nothing when he came, and at seven o’clock Booth breathed his last. He had on his person a diary, a large bowie-knife, two pistols, a compass and a draft on Canada for 60 pounds.”

John Wilkes Booth was only 26 years old when he was shot and killed. It’s hard to fathom that someone of Booth’s notoriety, flagrant hatred for the Federal Government, a known Confederate operative and his venomous contempt for President Lincoln, was not kept under a closer scrutiny and surveillance by agents, whose sole purpose was to protect the life of the Chief Executive. It could be that Lincoln’s Assassin was not just a Lost Cause Fanatic, but was really part and parcel of a larger political intrigue.

Bummer

04/23/13 Bummer- Just a comment on the timeline here….Lincoln’s Second Inauguration,set by law, was March 4, 1865. On the evening of April 11, 1865, Lincoln did speak to a public crowd that gathered at the White House. The previous day, he was also asked to make a speech but deferred until the next day and just asked the band to play “Dixie” to celebrate the surrender of Lee’s Army at Appomattox, VA. on April 9, 1865. Lincoln had difficulty reading his notes from the second floor window by candle light. His unusual speech was was prospective in tone and he did mention potential Negro sufferage for soldiers and some others. Booth was in the public crowd, heard the speech, and then decided to “kill” the President.

John,

Thanks for the correction, Bummer’s editing combined two sets of notes experiencing a typical “Senior Moment.” The “old guy” can use all the help he can get. Thanks for following.

Bummer remains,

Sincerely

Nice retelling, Bummer, but this is one of those things we’ll have to agree to disagree about. I think a lone nut like Booth was much more likely to succeed than a conspiracy – too many people to keep a secret and/or pay off. Booth is one of those historical characters I wish could have known the U.S. would have a black president one day; imagine how many gaskets he would have blown over Obama considering how much he hated Lincoln.

Louis,

Don’t think we disagree. The rush to judgement, the lack of credibility of the prosecution witnesses, Stanton and cast controlling the tribunal, all the stars and planets aligned, just left the “old guy” with to many “what ifs”. Having lived and researched all the mystery of JFK, RFK and MLK, “this student” will naturally question the anomalies of high profile political homocide. It might prove more healthy, than to just accept these events at face value. One can’t help but wonder, with Lincoln in obvious peril, where was the security? Obama would have blown Booth’s mind. Thanks for the dialogue, we are on the same track, Bummer probably has too much of the 60’s warp in his mindset.

Bummer