Lincoln’s BMI or Bureau of Military Information, was led by the Union spymaster George H. Sharpe. Sharpe’s bureau produced reports based on information collected from agents, prisoners of war, refugees, Southern newspapers, documents retrieved from battlefield corpses, and other sources. Sharpe started with about 70 agents who were carried on the rolls as “guides.” Major General Philip H. Sheridan, operating in the Shenandoah Valley, said the guides “cheerfully go wherever ordered, to obtain that great essential of success, information.” Of the 30 or 40 guides roaming the valley, 10 were killed in action. The secret to the success of the BMI and their stealthy operatives, was a complex method of identifying each other in the field and not knowing each others genuine names, even Lincoln was not aware of who they were, what their missions or where they were posted.

Lincoln’s BMI or Bureau of Military Information, was led by the Union spymaster George H. Sharpe. Sharpe’s bureau produced reports based on information collected from agents, prisoners of war, refugees, Southern newspapers, documents retrieved from battlefield corpses, and other sources. Sharpe started with about 70 agents who were carried on the rolls as “guides.” Major General Philip H. Sheridan, operating in the Shenandoah Valley, said the guides “cheerfully go wherever ordered, to obtain that great essential of success, information.” Of the 30 or 40 guides roaming the valley, 10 were killed in action. The secret to the success of the BMI and their stealthy operatives, was a complex method of identifying each other in the field and not knowing each others genuine names, even Lincoln was not aware of who they were, what their missions or where they were posted.

George Henry Sharpe, born on February 26, 1828, in Kingston, New York, his father, who died when George was two, was a wealthy merchant and the family was left well off. Sharpe graduated from Rutgers at 19, delivering the salutary address, in Latin,then went to Yale Law School and breezed through the New York bar exam at the age of 21, worked in New York City for the law firm of Bidwell and Strong, then traveled to Europe and worked for the U.S. legations in Vienna and Rome, where he acquired diplomatic and linguistic skills that his contemporaries would remark on throughout his life, at last returning to his hometown to set up his own law practice.

In 1861, he joined the Union army as a captain in the 1st Regiment of New York Volunteers. In 1862, he was appointed colonel of the 120th New York Infantry serving with distinction in late 1862. In early 1863, he was made a deputy provost-marshal general, and assigned to run Joseph Hooker’s new creation, the Union Intelligence Bureau; Sharpe soon changed the name to the Bureau of Military Information. In theory, he reported to provost general Marsena Patrick, but in practice, Patrick usually had little specific idea what Sharpe was up to or any real authority over him.

Sharpe had a very capable second in command, John C. Babcock, one of the few intelligence specialists to stay on after Pinkerton’s resignation. Unlike Pinkerton, Babcock was capable of accurate intelligence gathering, and particularly specialized in interrogating deserters and prisoners, and he became an expert on the order of battle for Lee’s army. Babcock, who had been an architect in Chicago before the war, was a civilian but was unofficially called “Captain Babcock.”

Sharpe was quick to exploit information from Virginia Unionists, utilizing an existing underground of Richmond Unionists, and gave particular weight to reports from Unionists Isaac Silver and Ebenezer McGee, located near Lee’s army just across the Rappahannock River. Reports from their network played a great role in formulating Hooker’s strategy for the Chancellorsville Campaign. Sharpe also employed many scouts, who penetrated Confederate lines to provide intelligence. Sharpe’s new BMI was soon providing accurate reports to Joseph Hooker’s headquarters, and based on these, Hooker formulated a brilliant strategy for the Chancellorsville Campaign. Hooker quickly learned that the BMI could not continue supplying this kind of detail to him during the active campaign, and as Hooker had sent nearly all of his cavalry on a fairly pointless raid, he was handicapped and allowed his imagination to run away with him. The campaign resulted in defeat, and Hooker, previously a pioneer in forming the BMI and gathering intelligence on the enemy’s army, began to disregard its reports, much to the disgust of Sharpe and his boss, Marsena Patrick.

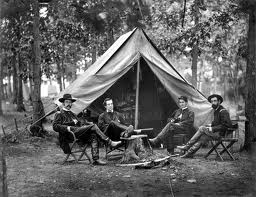

Sharpe sent his scouts, most of them noncommissioned officers and enlisted men, right into the enemy military camps. Some masqueraded as smugglers or Federal deserters and hung about a Rebel camp for a few days before vanishing back across the lines; others, even more daringly, donned Confederate uniforms and posed as soldiers separated from their units or members of irregular Confederate forces like John S. Mosby’s rangers. One especially daring BMI scout, Sgt. Milton W. Cline, managed to attach himself to a Confederate cavalry captain and rode the entire length of Lee’s lines a few days before the Battle of Chancellorsville. Sharpe requested that Federal military authorities send him for tens of thousands of dollars in captured Confederate currency, for him to give to his military scouts and civilian spies to use.

Sharpe sent his scouts, most of them noncommissioned officers and enlisted men, right into the enemy military camps. Some masqueraded as smugglers or Federal deserters and hung about a Rebel camp for a few days before vanishing back across the lines; others, even more daringly, donned Confederate uniforms and posed as soldiers separated from their units or members of irregular Confederate forces like John S. Mosby’s rangers. One especially daring BMI scout, Sgt. Milton W. Cline, managed to attach himself to a Confederate cavalry captain and rode the entire length of Lee’s lines a few days before the Battle of Chancellorsville. Sharpe requested that Federal military authorities send him for tens of thousands of dollars in captured Confederate currency, for him to give to his military scouts and civilian spies to use.

An example of Sharpe’s thoroughness can be seen in a report produced in May 1863 as General Robert E. Lee began moving troops in a march that ultimately ended at Gettysburg. The report begins with a detailed order-of-battle and later notes, “The Confederate army is under marching orders, and an order from General Lee was very lately read to the troops, announcing a campaign of long marches and hard fighting, in a part of the country where they would have no railroad transportation.”

Sharpe’s BMI continued to operate with remarkable efficiency for the Gettysburg Campaign, although they didn’t get everything right. On May 27th, shortly before

the campaign began, Sharpe submitted an incredibly accurate report to Hooker’s

headquarters reporting the likelihood that the rebel army was about to move, as

well as the position of its units. They continued supplying Hooker with generally correct information on the enemy’s movements, although sometimes arriving at the right conclusion for the wrong reasons.

When Meade ascended to the command of the Army of the Potomac, he had very good information on the enemy’s army from the BMI and his cavalry. Still, following the great victory at Gettysburg, the BMI did not fare particularly well under Meade. Meade took from them its task of analyzing the intelligence it collected from various sources and more or less assumed that task himself, a step back in the direction of McClellan-Pinkerton. Meade was a considerably more intelligent man than McClellan when it came to military realities, but undervalued the BMI; Sharpe’s boss Patrick was among those who referred to Meade as a “damned old goggle-eyed snapping turtle”, and Meade didn’t think the BMI offered him much that the cavalry didn’t.

When Grant came east, it was his intention to interfere as little as possible with Meade’s management of his army. The near-debacle in the Wilderness convinced Grant to take a more active role, making Meade feel like a glorified staff officer at times, but Meade still dealt with most administrative details of the army’s operation. Grant was, however, quite acquisitive when it came to talent, and very concerned with intelligence matters; so it isn’t surprising that by July, Grant had taken Sharpe onto his own staff, along with his BMI operation. Sharpe, not exactly running an army himself, had only a limited amount of field agents and had his hands full with Grant’s maneuver across the James; consequently, nobody was aware of the departure from Lee of Jubal Early’s corps until it defeated Hunter in the Valley. Grant promptly took steps to rectify this shortcoming with Sharpe, expanding Sharpe’s operation to the Valley. The BMI played a key role in the Valley campaign by monitoring movements of troops to and from the Valley; Sheridan also employed a service of scouts that supplied info both to Sheridan and Sharpe. The BMI did such a good job that the constant flow of information to the enemy was greatly lamented in Richmond.

When Grant came east, it was his intention to interfere as little as possible with Meade’s management of his army. The near-debacle in the Wilderness convinced Grant to take a more active role, making Meade feel like a glorified staff officer at times, but Meade still dealt with most administrative details of the army’s operation. Grant was, however, quite acquisitive when it came to talent, and very concerned with intelligence matters; so it isn’t surprising that by July, Grant had taken Sharpe onto his own staff, along with his BMI operation. Sharpe, not exactly running an army himself, had only a limited amount of field agents and had his hands full with Grant’s maneuver across the James; consequently, nobody was aware of the departure from Lee of Jubal Early’s corps until it defeated Hunter in the Valley. Grant promptly took steps to rectify this shortcoming with Sharpe, expanding Sharpe’s operation to the Valley. The BMI played a key role in the Valley campaign by monitoring movements of troops to and from the Valley; Sheridan also employed a service of scouts that supplied info both to Sheridan and Sharpe. The BMI did such a good job that the constant flow of information to the enemy was greatly lamented in Richmond.

Sharpe was breveted to brigadier-general of volunteers in December 1864, and later to major-general of volunteers in March 1865. His last task for Grant was to parole Lee’s army, obtaining oaths from each soldier that he wouldn’t take up arms against the United States again; he gallantly offered to skip this step for General Lee, who nevertheless insisted. Sharpe was mustered out in June of that year, returned home and rejoined his law firm.

He continued to perform intelligence duties for the government, traveling in Europe for the Secretary of State, investigating Americans living there who might have played a role in Lincoln’s assassination. He later spent time in Vermont investigating a plot by Irish nationalists to attack Canada. His former chief Grant remembered Sharpe when he became President; Sharpe became U.S. marshal for the southern district of New York, and won fame for battling and taking down the Boss Tweed political machine, jailing two of its ringleaders. He continued to play a role in state politics, and for nine years before his

death, was on the U.S. Board of General Appraisers. He was a member of the New York State Assembly in 1879, 1880, 1881 and 1882 and on July 2, 1890, President Harrison nominated Sharpe to serve as a Member of the newly created Board of General Appraisers.

George Henry Sharpe, died on January 13, 1900 in New York City and is buried at Wiltwyck Cemetery in Kingston, New York.

Lincoln’s BMI, Bureau of Military Information Chief, was not only a Union Spymaster, but George H. Sharpe was an unsung Civil War Hero and father of the strategic importance of Military Information and of its value in combating enemies of the United States.

Bummer

Thanks, Bummer, as much as I’ve read about the Civil War over the years, I really appreciate it when you post about a figure I know little or nothing about. Glad to hear about how effective Union intelligence gathering was. Usually you only hear about Confederate spies (Belle Boyd, Rose Greenhow). Now I know about George Sharpe too.

Louis,

Thanks for the read. Was excited to explore the details of Sharpe and his BMI. It seems that many of the unsung heroes of the Civil War were successful in their own minds and didn’t have the need or desire for political greatness. Similar to many of the social elite that were solicited into covert intelligence gathering during the 20th century, these obscure civil servants performed stealthy operations for the benefit of the welfare of the United States and that was their reward. The “old student” needs to do further research in order to unearth more of the tales and lore of the Civil War Intelligence network.

Bummer

Bummer