Ohio Abolitionist, Lucy Ware Webb Hayes, was not only the first Presidential wife to have graduated from college, but was brilliant, politically astute and clever enough to set the standard as President Hayes’ Original First Lady. Men of the 23rd Ohio Volunteer Infantry, who served under her husband’s command in the war, remembered her as Mother Lucy when she nursed the wounded back to health, cheered the homesick and comforted the dying. Under the influence of her maternal grandfather Isaac Webb, a representative in the Ohio legislature, she signed a pledge to forsake drinking any alcoholic beverages. She became a lifelong and fervent advocate of temperance, but resisted joining the organized movement. Similarly, despite believing strongly in her family’s radical abolitionism, Lucy Ware Webb was ambivalent about public activism on behalf of a social-political movement. She also expressed the view of equal intellectual capacity between the genders declaring; “Instead of being considered the slave of man, she is considered his equal in all things, and his superior in some.”

Ohio Abolitionist, Lucy Ware Webb Hayes, was not only the first Presidential wife to have graduated from college, but was brilliant, politically astute and clever enough to set the standard as President Hayes’ Original First Lady. Men of the 23rd Ohio Volunteer Infantry, who served under her husband’s command in the war, remembered her as Mother Lucy when she nursed the wounded back to health, cheered the homesick and comforted the dying. Under the influence of her maternal grandfather Isaac Webb, a representative in the Ohio legislature, she signed a pledge to forsake drinking any alcoholic beverages. She became a lifelong and fervent advocate of temperance, but resisted joining the organized movement. Similarly, despite believing strongly in her family’s radical abolitionism, Lucy Ware Webb was ambivalent about public activism on behalf of a social-political movement. She also expressed the view of equal intellectual capacity between the genders declaring; “Instead of being considered the slave of man, she is considered his equal in all things, and his superior in some.”

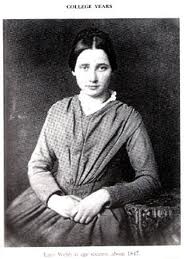

Lucy Ware Webb was born in Chillicothe, Ohio, to Dr. James Webb and Maria Cook on August 28, 1831. Two years later Dr. James Webb died during a cholera epidemic in Kentucky, where he had gone to free slaves he had inherited. In 1844 the Webb family moved to Delaware, Ohio. She had two brothers, Joseph Thompson Webb and James Dewees Webb, both older than their sister.

Lucy attended the Miss Baskerville School and the Chillicothe Female School in Ohio. She then attended Ohio Wesleyan Preparatory Department, in Delaware, Ohio, where her studies included, French, composition, grammar and penmanship. She next boarded away from home, at the Cincinnati Wesleyan Female College in Cincinnati, Ohio, where she was described as a “diligent” student. Lucy’s classes included, rhetoric, geometry, geology, astronomy, trigonometry, mental and moral science, German, French, drawing, painting, music.

Lucy attended the Miss Baskerville School and the Chillicothe Female School in Ohio. She then attended Ohio Wesleyan Preparatory Department, in Delaware, Ohio, where her studies included, French, composition, grammar and penmanship. She next boarded away from home, at the Cincinnati Wesleyan Female College in Cincinnati, Ohio, where she was described as a “diligent” student. Lucy’s classes included, rhetoric, geometry, geology, astronomy, trigonometry, mental and moral science, German, French, drawing, painting, music.

Rutherford Birchard Hayes started practicing the law in Cincinnati, Ohio when he was 27 years old. Lucy first met Rutherford B. Hayes on the campus of Ohio Wesleyan University in Delaware. Hayes was nine years older than Lucy, however references to her appeared in his diary; “Her low sweet voice is very winning … a heart as true as steel…. Intellect she has too…. By George! I am in love with her!”

The mother of Hayes, a friend of Lucy’s mother, had long encouraged a match between the two, being especially drawn to Lucy Webb’s moral and religious character. The young couple was engaged for a year and on December 30, 1852, they wed in the Webb family home, in Cincinnati, Ohio. A local newspaper chronicled the ceremony; “the ‘radiant’ bride looked beautiful in her white-figured satin dress, simply tailored with a full skirt pleated to a fitted bodice. She wore a floor-length veil, fastened with orange blossoms. It accented the glistening blackness of her hair and the slimness of her figure.” The couple eventually had 8 children, seven sons and one daughter.

The mother of Hayes, a friend of Lucy’s mother, had long encouraged a match between the two, being especially drawn to Lucy Webb’s moral and religious character. The young couple was engaged for a year and on December 30, 1852, they wed in the Webb family home, in Cincinnati, Ohio. A local newspaper chronicled the ceremony; “the ‘radiant’ bride looked beautiful in her white-figured satin dress, simply tailored with a full skirt pleated to a fitted bodice. She wore a floor-length veil, fastened with orange blossoms. It accented the glistening blackness of her hair and the slimness of her figure.” The couple eventually had 8 children, seven sons and one daughter.

Before the Civil War, Lucy Hayes supported the abolition and women’s rights movements. Hayes’ sister-in-law inspired her to play an active role in both movements. After her sister-in-law’s death in 1855, Hayes became less involved in the women’s movement, but she remained committed to abolitionism.

Lucy and Rutherford respected each other’s ideals and goals. When he practiced law in Cincinnati, Rutherford, influenced by Lucy’s anti-slavery sentiments, defended runaway slaves who had crossed the Ohio River from Kentucky. Lucy supported Rutherford’s decision to volunteer for military service during the Civil War. Her husband served as the commander of the Twenty-third Ohio Volunteer Infantry Regiment. As often as she could, Lucy, sometimes with her mother and children, visited Rutherford in the field. She often assisted her brother, Dr. Joe Webb, in caring for the sick.

Lucy took an active interest in her husband’s political career. When Rutherford served in the United States Congress, Lucy worked for the welfare of children and veterans. During his tenure as governor of Ohio, she secured funding for an orphanage for the children of Civil War veterans.

After serving as governor of Ohio, he was nominated by the Republican party for the presidency of the United States. It was not a landslide election, but Rutherford won and the couple headed off for the White House with small children in tow. The halls of the capital were often filled with laughter and the sound of children’s voices.

When Hayes was elected president in 1876, it was one of the closest elections in history. At first it looked like Hayes had lost. He had fewer electoral votes than his Democratic rival Samuel Tilden. However, several electoral votes were in dispute. Congress had to decide who these votes would go to and they picked Hayes.

The Democrats from the southern states were not happy with this. They said Hayes and the Republicans had cheated. In order to work out a compromise, Hayes and the Republicans agreed that federal troops would be removed from the South. In return, the South agreed to accept Hayes as president. This signaled the end of the Reconstruction.

Lucy became one of the most beloved first ladies in American history. Her sweet nature charmed all who came to know her. Even though she had her strong convictions on issues such as “no alcohol served in the White House” the nation fell under her spell. Nicknamed “Lemonade Lucy,” she made no apologies for her beliefs. There were some among the Washington power elite who complained at first, but as one contemporary declared: “Lucy’s courage in adopting a controversial policy for White House entertaining helped to convince people of the honesty and sincerity of the president and the First Lady.” With her tiny stature, her beautiful black hair, and kind brown eyes, a Washington reporter chronicled; “Lucy Hayes was one of the most personally popular of all of America’s First Ladies” and as reporter, Mary Clemmer Ames, related, “Mrs. Hayes’s strong healthful influence gives the world assurance of what the next century’s women will be.”

Lucy became one of the most beloved first ladies in American history. Her sweet nature charmed all who came to know her. Even though she had her strong convictions on issues such as “no alcohol served in the White House” the nation fell under her spell. Nicknamed “Lemonade Lucy,” she made no apologies for her beliefs. There were some among the Washington power elite who complained at first, but as one contemporary declared: “Lucy’s courage in adopting a controversial policy for White House entertaining helped to convince people of the honesty and sincerity of the president and the First Lady.” With her tiny stature, her beautiful black hair, and kind brown eyes, a Washington reporter chronicled; “Lucy Hayes was one of the most personally popular of all of America’s First Ladies” and as reporter, Mary Clemmer Ames, related, “Mrs. Hayes’s strong healthful influence gives the world assurance of what the next century’s women will be.”

She believed in education and allowed White House servants to take time off from their duties to attend school. Lucy Hayes wanted women to have greater access to education. She believed that women needed to be educated before receiving the right to vote. She also donated up to one thousand dollars per month to assist the homeless. She also started what has become a tradition: when the children of Washington were banned from rolling their Easter eggs on the Capitol grounds, Lucy invited them to use the White House lawn on the Monday following Easter. While Lucy Hayes was admired by the American people, she did not enjoy being First Lady. She was thankful when Rutherford Hayes’s term of office ended in 1881.

Rutherford and Lucy returned to their Fremont, Ohio, home, Spiegel Grove, in 1881. Lucy Hayes intended to lead a peaceful and private life at their Spiegel Grove estate. She did, however, attend the centennial celebrations of the presidency in May of 1889 in New York at the request of then-incumbent First Lady Caroline Harrison. Mrs. Hayes also assumed presidency of the Methodist Missionary Society. In that capacity, the former First Lady began delivering a series of startling speeches at their annual convention, disparaging non-Anglo races as inferior in the commitment to Christianity, higher education and population control. It represents an aspect of her life at odds with the character reflected in her private letters and remarks.

Lucy Ware Webb Hayes died of a stroke on June 25, 1889, two years before the death of Rutherford. They were both buried at Fremont City Cemetery, in Ohio, but were both re-interred at Spiegel Grove in 1915.

Ohio Abolitionist, Lucy Ware Webb Hayes, was not only President Hayes’ Original First Lady, but set an example for future women in politics, world-wide, proving that the woman more than often is the real power behind the throne and that her actions definitely speak louder than words or policy.

Bummer