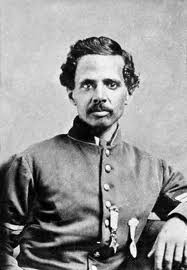

Cincinnati Patriot, Powhatan Beaty, was not only an aspiring actor, but a fearless Black Union Hero, who was also a Medal of Honor recipient. On September 5, 1862, Beaty, along with 706 other African-American men, was forced to join Cincinnati’s Black Brigade, after Confederate troops repeatedly threatened the city. Powhatan Beaty later served in the Union Army’s 5th United States Colored Infantry Regiment throughout the Richmond–Petersburg Campaign, during which the Cincinnati Hero’s bravery would be rewarded with the Medal of Honor.

Cincinnati Patriot, Powhatan Beaty, was not only an aspiring actor, but a fearless Black Union Hero, who was also a Medal of Honor recipient. On September 5, 1862, Beaty, along with 706 other African-American men, was forced to join Cincinnati’s Black Brigade, after Confederate troops repeatedly threatened the city. Powhatan Beaty later served in the Union Army’s 5th United States Colored Infantry Regiment throughout the Richmond–Petersburg Campaign, during which the Cincinnati Hero’s bravery would be rewarded with the Medal of Honor.

Powhatan Beaty, was born on October 8, 1837, in Richmond, Virginia. Beaty, who was born a slave, was either freed in Richmond or shortly after he relocated to Cincinnati, Ohio, in 1849. After his move to Cincinnati, he attained a common education of the era and became interested in acting. Powhatan began working as a cabinet maker’s apprentice, studying acting and elocution in his free time, under the tutelage of veteran stage actor, James E. Murdock of Philadelphia.

In 1862, Cincinnati was in a panic, fearing a Confederate attack, the men of the city banded together to build fortifications. Included in this force was the Black Brigade, originally impressed with building fortifications for the city and digging tunnels beneath the Ohio River in northern Kentucky, work that the white brigades were not asked to perform. For the next fifteen days, they cleared forests, constructed forts, magazines and roads, and dug trenches and rifle pits. The brigade was disbanded on September 20, with the threat of attack subsiding.

On June 5, 1863, at the age of twenty-four, Beaty, left Cincinnati and enlisted as a private in the Union Army at Camp Delaware, Ohio, an all-black recruiting camp for African-American enlistees. Beaty enlisted for three years and only two days later, he was promoted to first sergeant, one of the highest ranks an African-American soldier could attain. He was placed in charge of a squad of forty-seven other recruits and ordered to report to Columbus, Ohio, from where they would be sent to Boston. Upon arriving in Columbus on June 15, however, they learned that the Massachusetts regiments were full and unable to accept their service. The Governor of Ohio, David Tod, requested permission from the Department of War to form a regiment of African-Americans. Permission was granted, and on June 17, Beaty and his squad became the first members of the 127th Ohio Volunteer Infantry, later re-designated the 5th United States Colored Troops. After several months of training and organization the unit set out for Virginia.

Powhatan Beaty and his troopers served valiantly during the Union’s campaign at Richmond and Petersburg in 1864, promoted to first sergeant, Beaty led his men into the center of the Confederate fortifications at New Market Heights, on September 29, 1864. These defenses consisted of two lines of abatis and one line of palisades, manned by Brigadier General John Gregg’s Texas Brigade. The attack was met with intense Rebel fire and was turned back after reaching the front line. During the retreat, Company G’s color bearer was killed; Beaty returned under enemy fire to retrieve the flag. Of Company G’s eight officers and eighty-three enlisted men who entered the battle, only sixteen enlisted men, including Beaty, survived the attack unwounded. With no officers remaining, Beaty took command of the company and led it through a second charge. This attack successfully drove the Confederates from their positions, costing G Company 3 more killed. By the end of the battle, over fifty percent of the black division had been killed, captured, or wounded. For his actions, Beaty was commended on the battlefield by General Benjamin Butler and seven months later, on April 6, 1865, awarded the Medal of Honor. His Medal of Honor citation reads,

“Took command of his company, all the officers having been killed or wounded, and gallantly led it.“

After the Civil War, Beaty briefly worked as a porter on the Mississippi River steamboat City of Vicksburg. Upon returning to Cincinnati, Beaty went back to cabinet making and again took up acting. In the 1870s he began to perform publicly and near the end of the decade he attained some recognition for his theatrical performances.

Throughout the 1880s, Beaty performed with the famed African-American leading actress Henrietta Vinton Davis in Cincinnati, Washington, D.C., and Philadelphia. Powhatan Beaty reportedly received high praise for his roles in Macbeth, Richard III, and Ingomar, the Barbarian in the New York Globe. In 1880 Beaty wrote a play about the transition from slavery to freedom titled Delmar; or Scenes in Southland. The play was performed publicly in 1881 with Beaty starring in the leading role as the plantation owner. In 1888, Beaty became the drama director of the Literary and Dramatic Club of Cincinnati, a club that he had helped form. He gave public readings for charitable causes and became a well-known elocutionist among the African-American community of Cincinnati.

Powhatan Beaty, died on December 6, 1916, at the age of 79 and is buried at the Union Baptist Cemetery in Cincinnati, Ohio.

Cincinnati Patriot, Powhatan Beaty, was not only a Black Union Hero, but an inspiration to all struggling minorities, an example of triumph over adversity.

Bummer