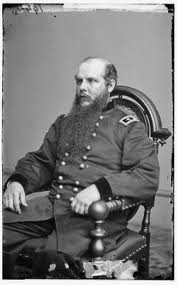

Schofield, a Political General, during the Civil War, gained rank and recognition, not through his leadership qualities or heroic deeds, but by gaining favor as a Halleck Yes Man. Another renowned contemporary, General John Pope stated that Schofield, “could stand steadier on the bulge of a barrel than any man who ever wore shoulder straps.” Some military leaders never gain the recognition that their battle exploits deserve, others receive historic reverence based on a political and chain of command subservience. John Schofield was one of the few army generals, who rose through the ranks to battlefield command, without the benefit of significant combat leadership experience.

Schofield, a Political General, during the Civil War, gained rank and recognition, not through his leadership qualities or heroic deeds, but by gaining favor as a Halleck Yes Man. Another renowned contemporary, General John Pope stated that Schofield, “could stand steadier on the bulge of a barrel than any man who ever wore shoulder straps.” Some military leaders never gain the recognition that their battle exploits deserve, others receive historic reverence based on a political and chain of command subservience. John Schofield was one of the few army generals, who rose through the ranks to battlefield command, without the benefit of significant combat leadership experience.

John McAllister Schofield, born September 29, 1831, in Gerry, New York, moved with his parents at the age of twelve to Freeport, Illinois in 1843. After a public school education, Schofield became a surveyor in northern Wisconsin and taught school. In 1849, he was offered an appointment as a cadet at the United States Military Academy and graduated 7th in his class in 1853, along with Philip H. Sheridan, James B. McPherson and John B. Hood. Before his graduation Schofield was dismissed for an incident of lewd behavior towards several cadet candidates that Schofield was responsible for, which cost the candidates a chance of passing their entrance exams. In reporting the affair to the Secretary of War, Schofield’s offense was called disgraceful and exemplary punishment was recommended. The Secretary agreed and Schofield was dismissed from the Academy. Two weeks later this decision was reconsidered, when Schofield petitioned Senator Stephen A. Douglas and the matter was referred to a court of inquiry, where upon the dismissal was rescinded. A dissenting member of this inquiry was a future superior officer of Schofield, Lieutenant George H. Thomas.

In July in 1853, John Schofield was commissioned a second lieutenant in the Second Artillery, United States Army, and was assigned to serve in South Carolina. After two years in the South, Schofield was promoted to first lieutenant and reassigned to West Point, where he served as an assistant professor of natural and experimental philosophy until 1860. While at the academy, Schofield married Harriet Bartlett in 1857. In 1860, Schofield was granted a leave from the army, and he took a position as professor of physics at Washington University, St. Louis, where he remained until the Civil War began.

At the beginning of the war, Schofield served as a major in the 1st Missouri Infantry, charged with mustering Missouri troops. Later in 1861, he served as Assistant Adjutant-General to General Nathaniel Lyon, organizing the forces of the Union Army in Missouri. Schofield participated in the Camp Jackson affair in St. Louis in May 1861 and in June was named chief of staff of Lyon’s Army of the West. In the summer of 1861 he assisted in the campaign to Jefferson City, the skirmish at Boonville, and the march to Springfield. In August, he commanded the 1st Missouri Volunteer Infantry at the Battle of Wilson’s Creek. General Lyon was killed at Wilson’s Creek and in 1892, as commander-in-chief of the army, Schofield recommended himself and received the Medal of Honor, apparently for an attack that he ordered at Wilson’s Creek, that no one after the war remembered.

Henry Halleck assumed command at St. Louis in November of 1861. On November 21, 1861, Schofield was promoted to brigadier general, and placed in charge of all the Union militia in Missouri. When Halleck left St. Louis to command the advance to Corinth, Schofield assumed the administration of most of Missouri. After the Corinth campaign, Halleck went to Washington and became Commander-in-Chief of the Army and Schofield was placed in charge of the Army of the Frontier. He was then promoted to Major General of volunteers on November 29, 1862, although the Senate did not finally confirm the appointment until May 12, 1863.

In February 1864 he was assigned command of the Army of the Ohio. Beginning in April 1864 his command, designated the XXIII Corps, took part in Sherman’s Atlanta campaign seeing action at Resaca, Dallas, Kennesaw Mountain, and Atlanta. When Sherman left Atlanta, Schofield and his corps became part of the forces being organized under George H. Thomas to counter Hood’s invasion of Tennessee. Schofield was in command at Franklin on November 30 when Hood’s army was defeated. For his services at Franklin, Schofield was appointed brigadier general in the regular army and on March 13, 1864 was breveted major-general in the regular army.

In February 1864 he was assigned command of the Army of the Ohio. Beginning in April 1864 his command, designated the XXIII Corps, took part in Sherman’s Atlanta campaign seeing action at Resaca, Dallas, Kennesaw Mountain, and Atlanta. When Sherman left Atlanta, Schofield and his corps became part of the forces being organized under George H. Thomas to counter Hood’s invasion of Tennessee. Schofield was in command at Franklin on November 30 when Hood’s army was defeated. For his services at Franklin, Schofield was appointed brigadier general in the regular army and on March 13, 1864 was breveted major-general in the regular army.

Schofield was moved to fight under Sherman in North Carolina. He helped captured Wilmington and fought at the battle of Kinston before meeting up with Sherman on March 23, 1865 in Goldsboro. Working together with Sherman, Schofield led the Department of North Carolina until the surrender of Johnston at Durham Station.

After the Civil War, John Schofield served as a diplomatic emissary to France from June 22, 1865, to August 16, 1866, negotiating the withdrawal of French troops from Mexico. Upon his return, Schofield served briefly as Secretary of War under President Andrew Johnson. On March 4, 1869, he was promoted to major-general in the regular army. Schofield was then sent to the Hawaiian Islands and recommended that the United States establish a military base at Pearl Harbor. In 1876 Schofield was named as Superintendent of the United States Military Academy, where he remained until 1881. Upon leaving West Point, Schofield commanded the Military Division of the Pacific, the Division of the Missouri and the Division of the Atlantic. On August 14, 1888, Schofield was promoted to commanding general of the United States Army. Later that year, his first wife, Harriet, died and Schofield married his second wife, Georgia Kilbourne, in 1891. Schofield was promoted to lieutenant-general on February 25, 1895, before retiring from active service on his sixty-fourth birthday, September 29, 1895.

After the Civil War, John Schofield served as a diplomatic emissary to France from June 22, 1865, to August 16, 1866, negotiating the withdrawal of French troops from Mexico. Upon his return, Schofield served briefly as Secretary of War under President Andrew Johnson. On March 4, 1869, he was promoted to major-general in the regular army. Schofield was then sent to the Hawaiian Islands and recommended that the United States establish a military base at Pearl Harbor. In 1876 Schofield was named as Superintendent of the United States Military Academy, where he remained until 1881. Upon leaving West Point, Schofield commanded the Military Division of the Pacific, the Division of the Missouri and the Division of the Atlantic. On August 14, 1888, Schofield was promoted to commanding general of the United States Army. Later that year, his first wife, Harriet, died and Schofield married his second wife, Georgia Kilbourne, in 1891. Schofield was promoted to lieutenant-general on February 25, 1895, before retiring from active service on his sixty-fourth birthday, September 29, 1895.

Schofield spent his remaining years writing his military memoirs, Forty-Six Years in the Army and actively engaged in veteran organizations.

John M. Schofield died from a cerebral hemorrhage on March 4, 1906, in St. Augustine, Florida, and was buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

A successful career, whether in politics or the military, is based on whom and what one knows. In regards to John M. Schofield, after nearly 150 years and a review of his correspondence with Halleck, Grant and Sherman, it appears that Schofield was not above character assassination, for either personal or vengeful gain, regarding George Thomas and other contemporaries. The Medal of Honor for “conspicuous gallantry” at Wilson’s Creek smacks of self aggrandizement. Schofield learned how to work the military and political machine and was definitely a Yes Man to more than just Halleck.

Bummero command the advance t

Bummer, I’m a little bit confused here on what Halleck did for Schofield. It looks like he just followed Halleck because he happened to be his second-in-command whenever he got promoted. Was Halleck close to Andrew Johnson? Is that the reason Schofield got dragged into that battle between Johnson and Stanton? Finally, what was this lewd act that ended Schofield’s West Point career?

Louis,

A poor write on this end. Knew the story that needed to be told, just couldn’t paint the portrait. Let’s try to make to simple. The scandle at West Point involved Schofield “permitting his class to be turned into a burlesque by making the uses of their procreative and eliminative organs the subject of a blackboard examination.” This event appalled the military elite of the era, resulting in his dismissal. Schofield had the political connections, whoever they were, in addition to Douglas, in order for the inquiry to find in his favor. Schofield was reinstated and and even taught at the Point later on. George Thomas was one of the dissenting votes. It is surmised that some in military circles had long memories, that haunted Schofield the rest of his career. Schofield orchestrated his military destiny in Missouri, through recruiting and initially supporting Lyon, a true gentleman and hero. Lyon’s death at Wilson’s Creek, gave Schofield free rein in Missouri and with Halleck in the wings, as his superior, he started grooming the new commander, gaining his ear. A good example of his early character assassinations, is evidenced by his reports to Halleck, regarding Samuel Curtis’ supposed ineptness at Pea Ridge. What Schofield practised early on, was his unwavering support of Halleck, in his military climb to the ultimate command, no matter the truth or fact. Telling Halleck what he wanted to hear, regarding Grant and Sherman at Shiloh, supporting Halleck’s decisions at Corinth and later his communications to Halleck, Grant and Sherman in regards to General Thomas, revenge for his opposition at West Point. Although fighting in no other major battles, he shows up in 1864 in Tennessee a Major General, and is appointed to command the Army of the Ohio. It pays to have friends. It wasn’t just what Schofield did, it was the rumor and enuendo in written support of Halleck’s command decisions, especially in regards to Thomas and his in activity in Tennessee. Who was the real hero in Tennessee? According to Schofield, it was himself and surely not Thomas. Halleck was calling the shots and with Schofield’s support from the field, his actions were justified and bolstered Schofield’s esteem. In his memoir, Schofield relates,

“Time works legitimate “revenge”, and makes all things even. When I was a boy at West Point I was court-martialed for tolerating some youthful “deviltry” of my classmates, in which I took no part myself, and was sentenced to be dismissed. Thomas, then already a veteran soldier, was a member of the court, and he and one other were the only ones of the thirteen members who declined to recommend that the sentence be remitted. This I learned in 1868, when I was Secretary of War. Only twelve years later I was able to repay this unknown stern denial of clemency to a youth by saving the veteran soldier’s army from disaster, and himself from the humiliation of dismissal from command on the eve of victory.”

As far as can be researched, Schofield’s Medal of Honor, for gallantry at Wilson’s Creek is not even mentioned in his memoirs and no one but Schofield was alive to verify or deny his heroism at Wilson’s Creek. After 150 years, who knows? He sure enjoys the company of many dynamic and brave patriots of the Civil War. Both Halleck and Schofield were adept at playing both sides, to their own benefit and advancement. I would doubt if either would harm their career or legacy by seriously intervening between Johnson and Stanton.

Schofield had a long run and successful military career, revered by many. However, the “old guy” has his doubts.

Bummer

Given that he did graduate from West Point and served after that, why do you label Schofield a political general? I consider Banks and Butler to be political generals since they were politicians that were made generals for political reasons.

Michael,

The politics of the military machine and the government work in much the same way. Banks and Butler were political generals in their own right. Schofield worked his superiors in much the same way as a professional politician. Thanks for the input!

Bummer